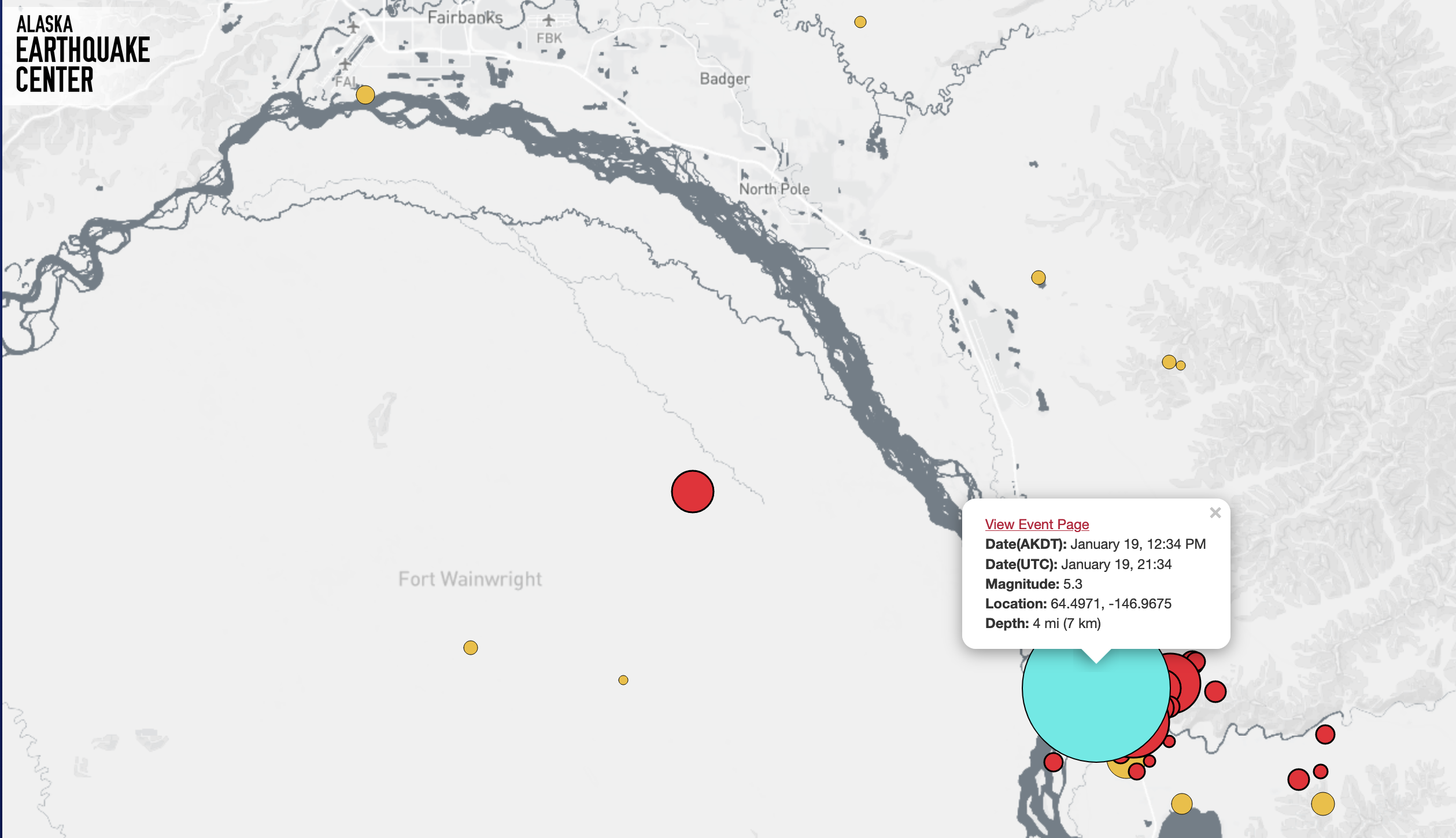

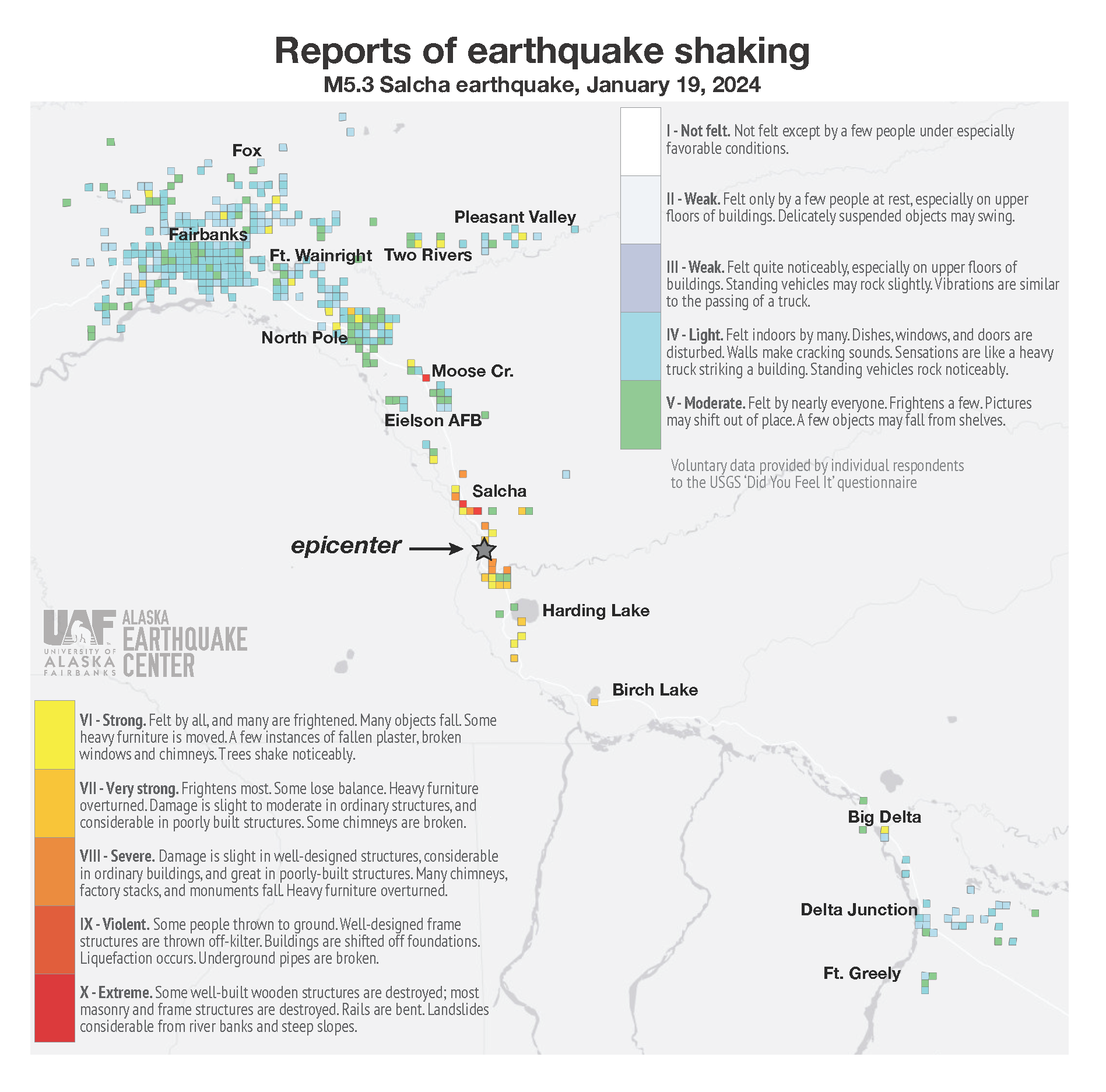

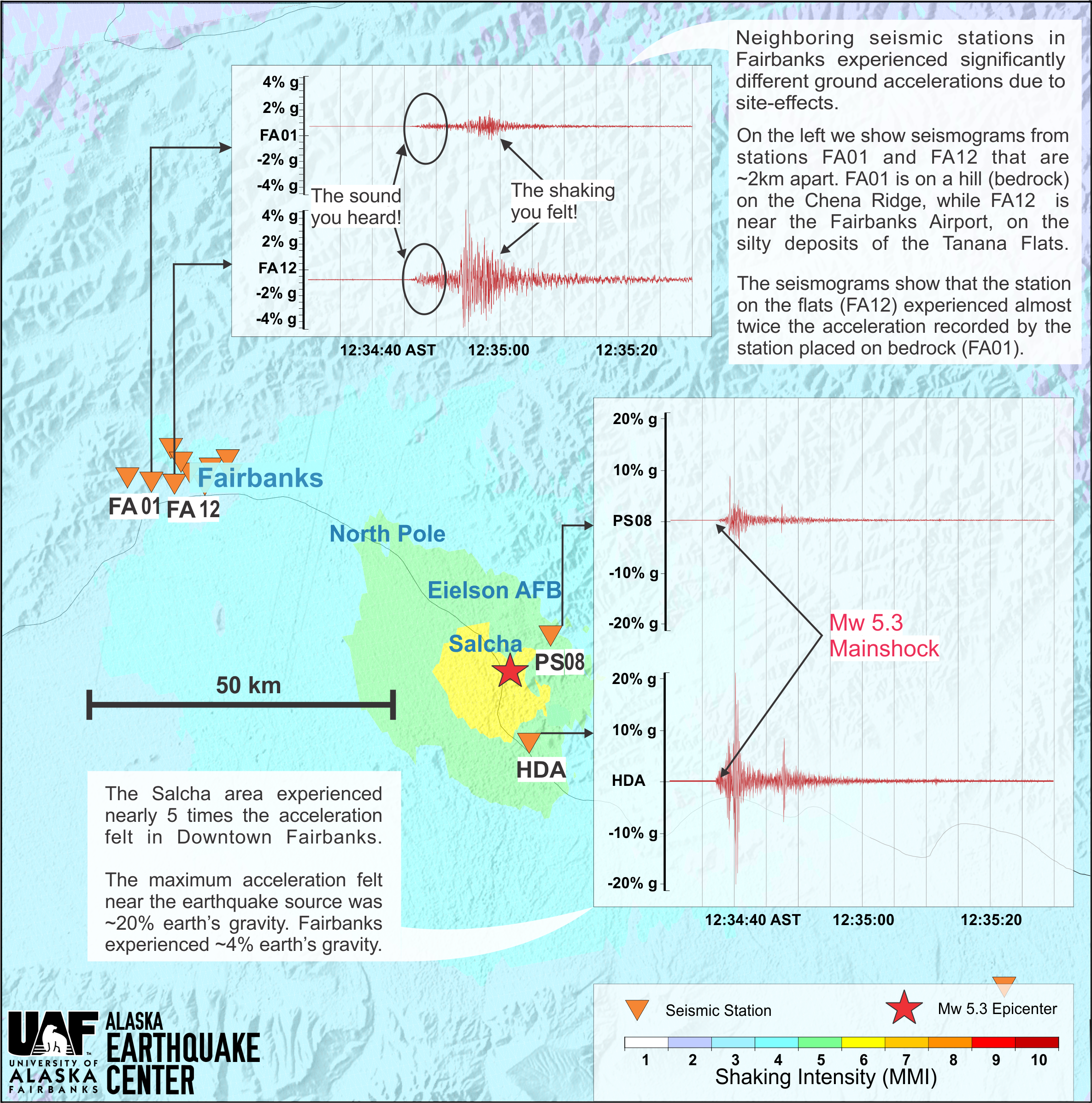

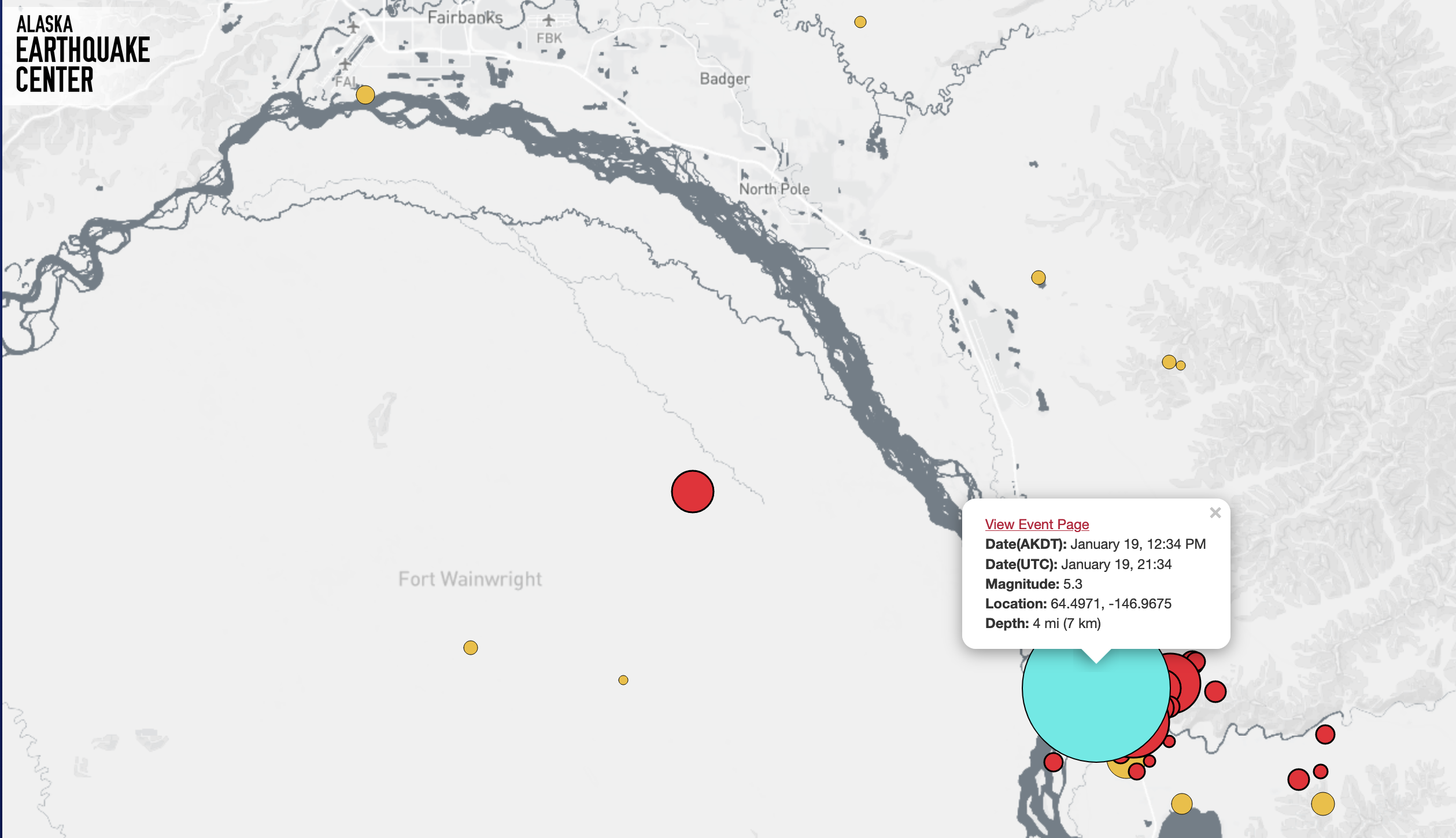

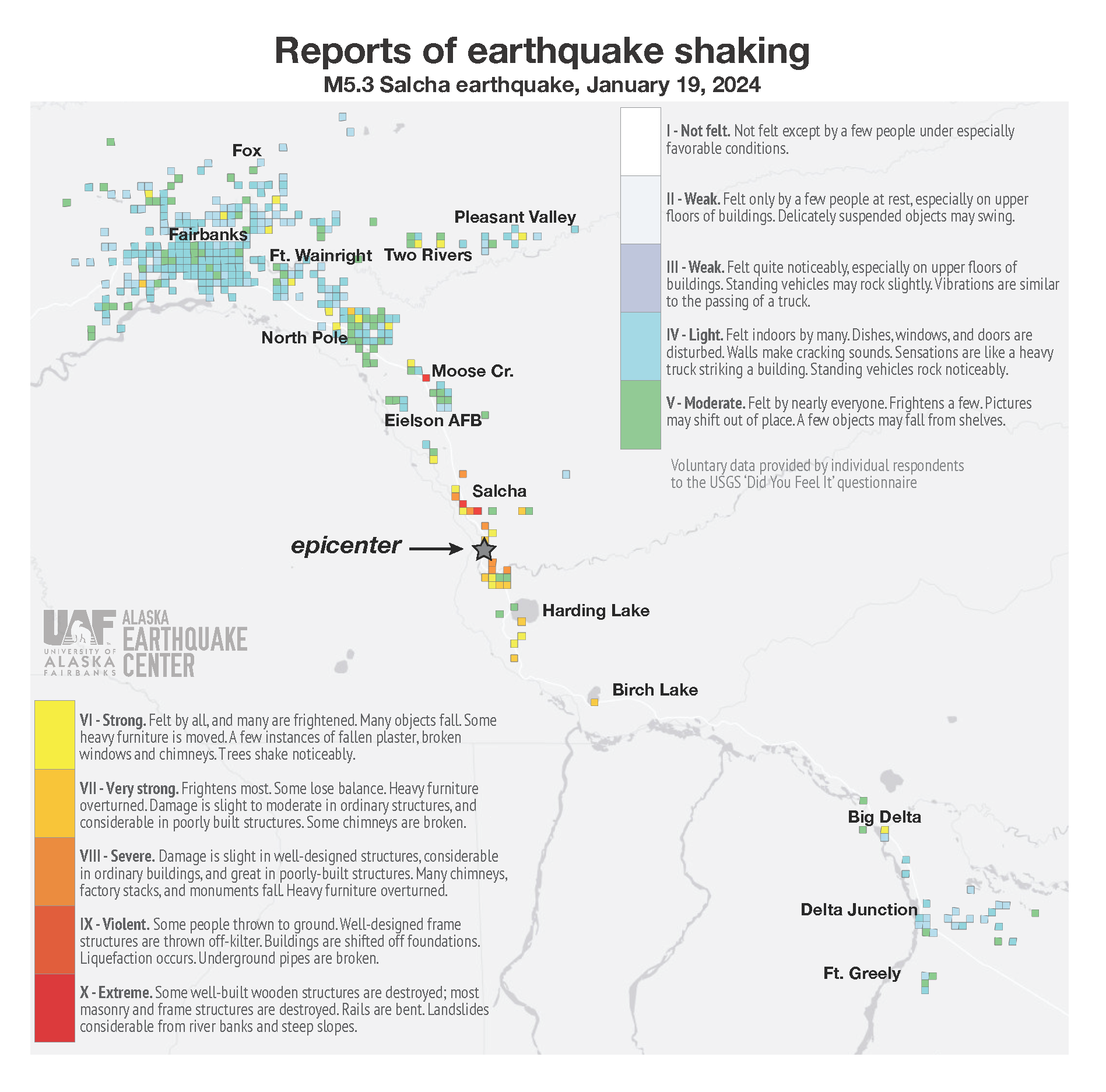

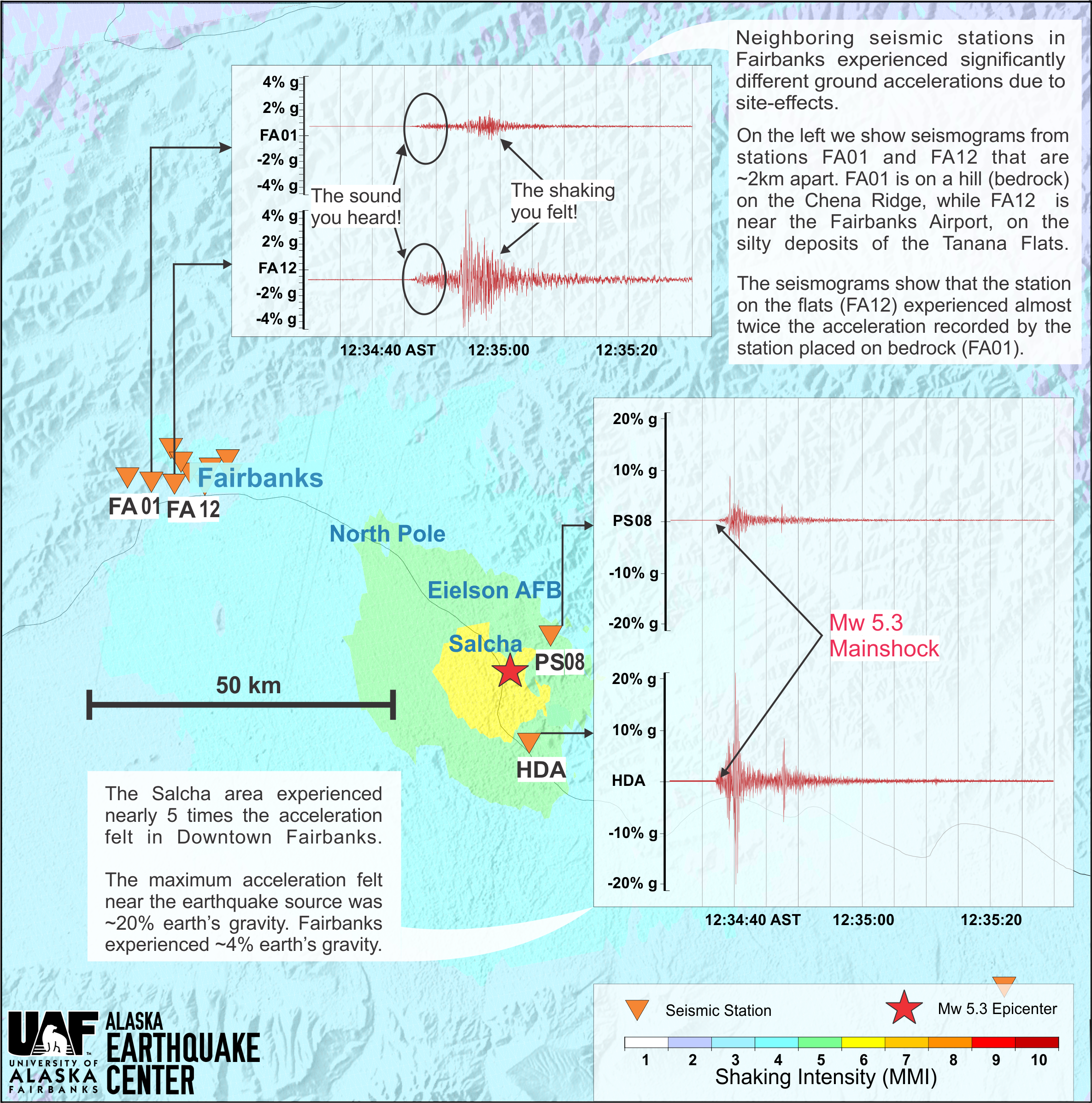

The Alaska Earthquake Center was in the midst of giving a tour to a group of international Arctic Weather Workshop attendees when suddenly, the ground started to shake. When it continued to shake, everyone realized this was more than just a truck rumbling by. A magnitude 5.3 earthquake struck under Salcha, a small community about 30 miles (50 km) southeast of Fairbanks (Figure 1). The event was shallow, at 4 miles (7 km) deep, which means it was felt more intensely than if it was deeper in Earth’s crust.

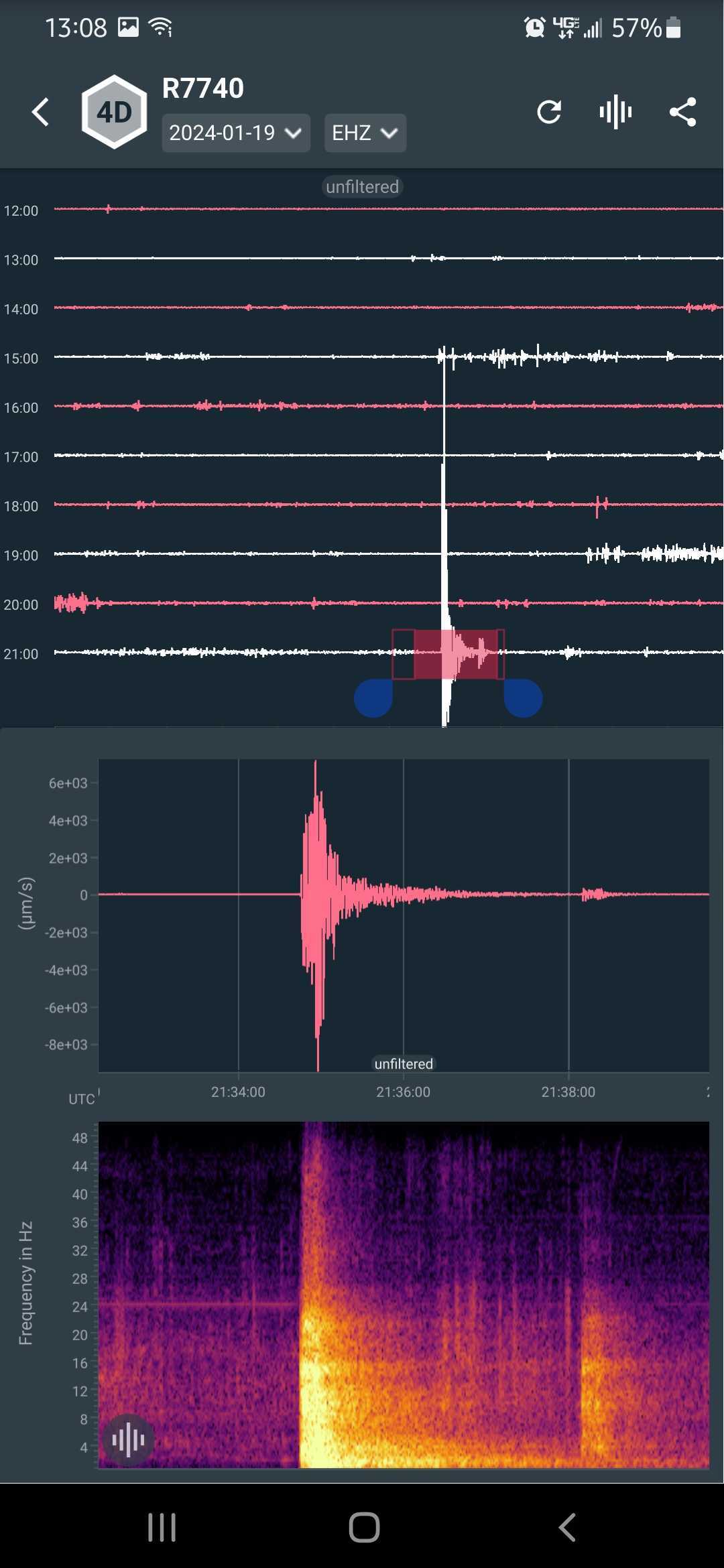

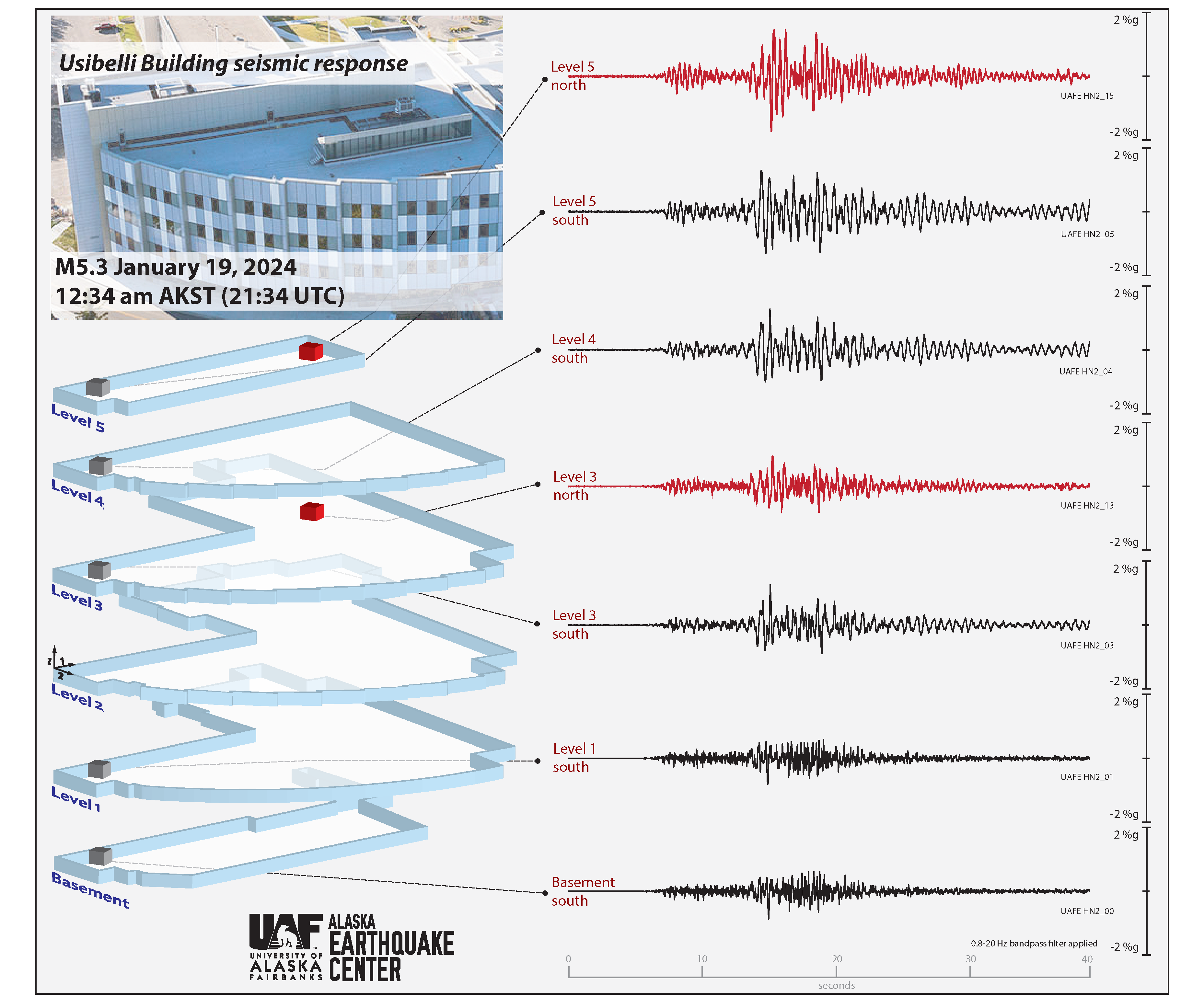

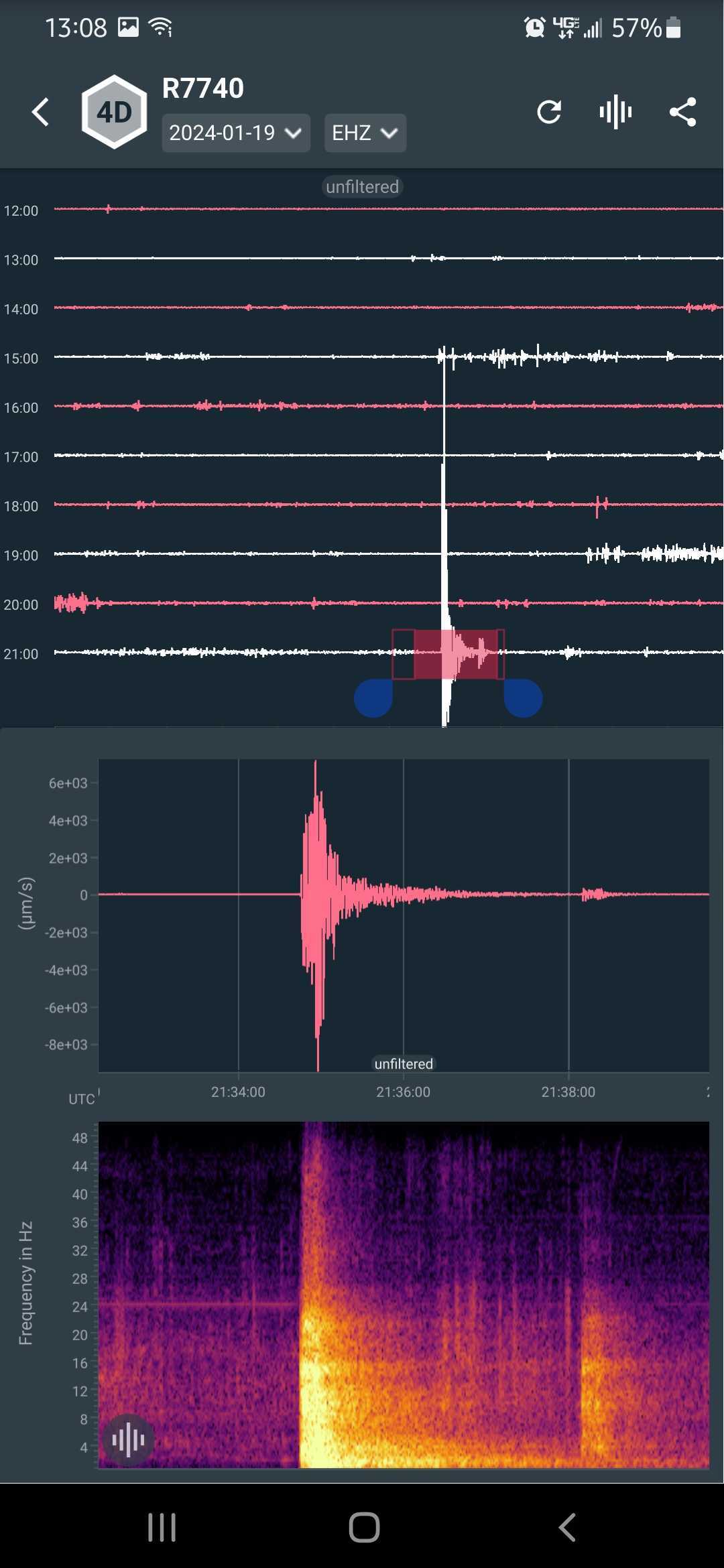

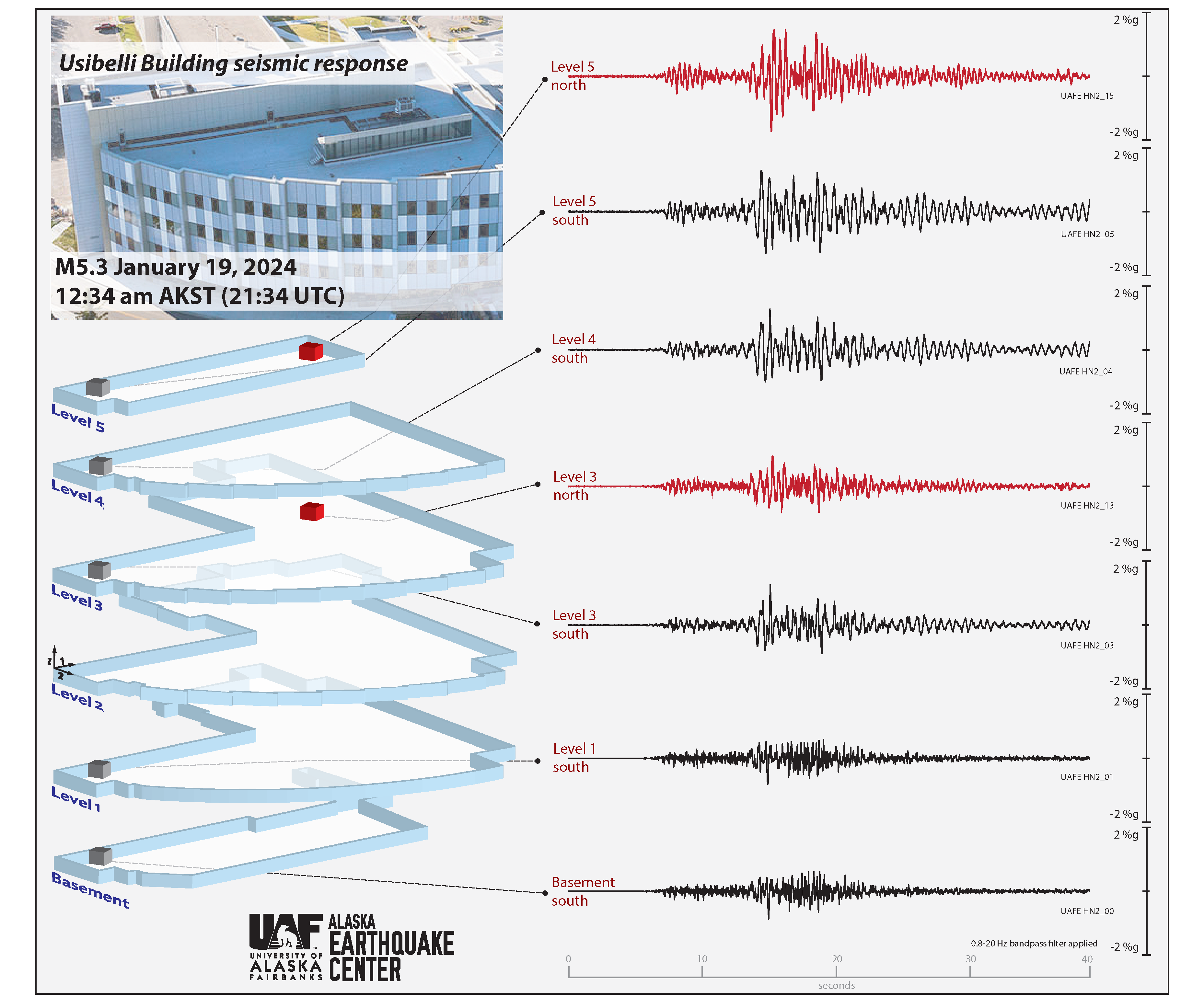

The earthquake proceeded in typical earthquake fashion—gentle rumbling that grew into more significant shaking, along with some rolling (Figure 2). Office computers swayed on the desks. The shaking lasted for 5–10 seconds, after which everyone looked at each other, startled, and then several people on the tour exclaimed that it was the first earthquake they had ever felt.

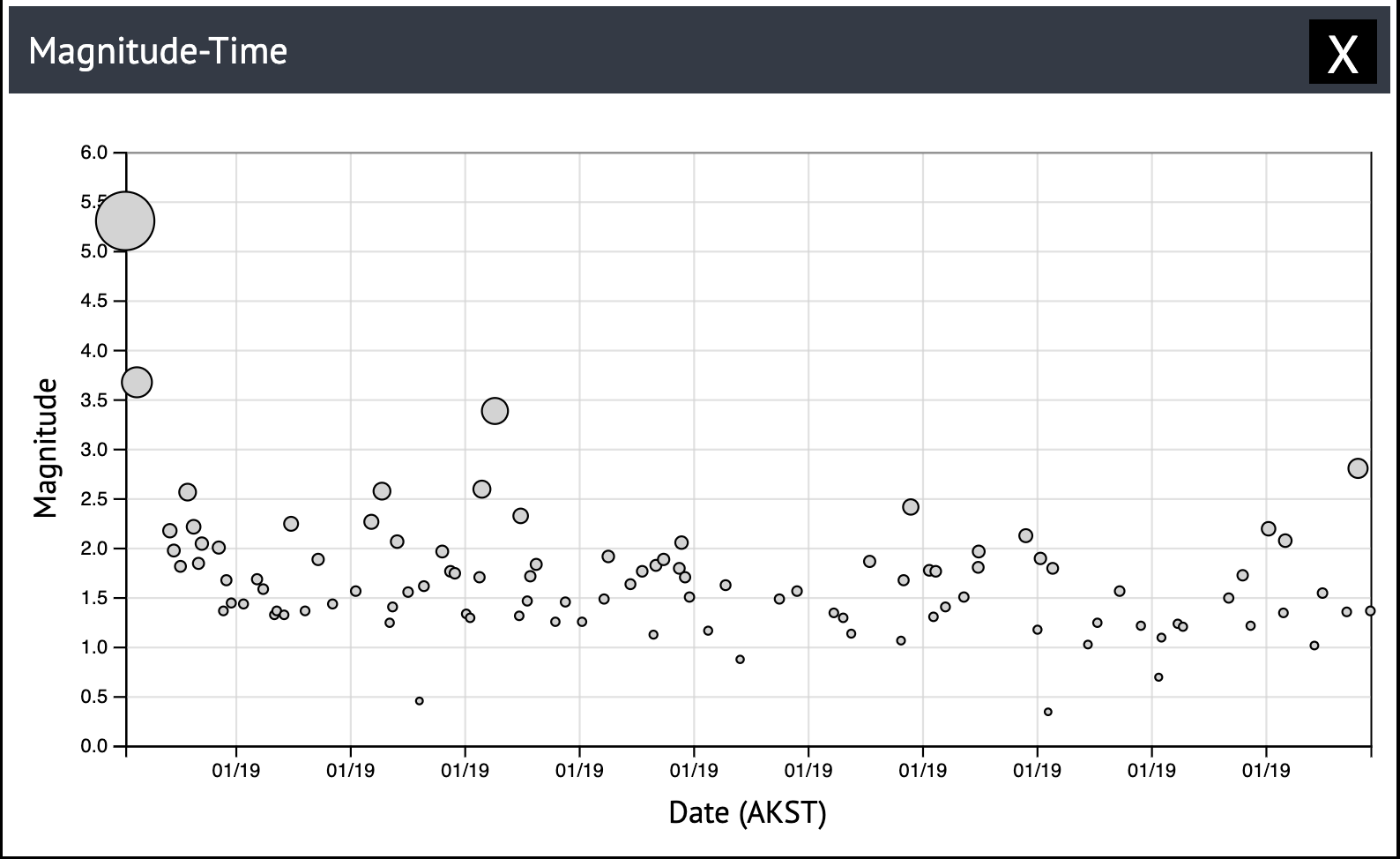

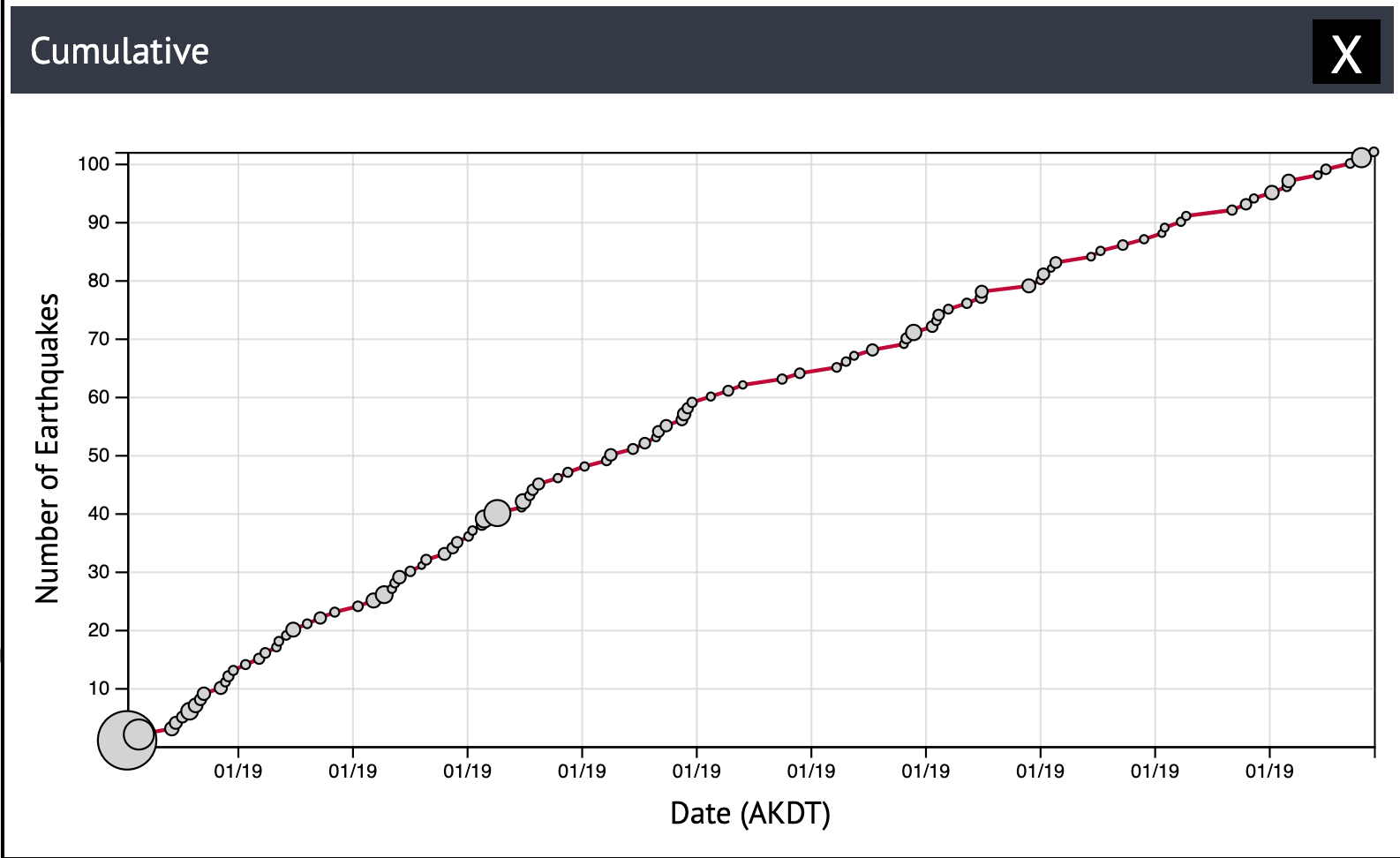

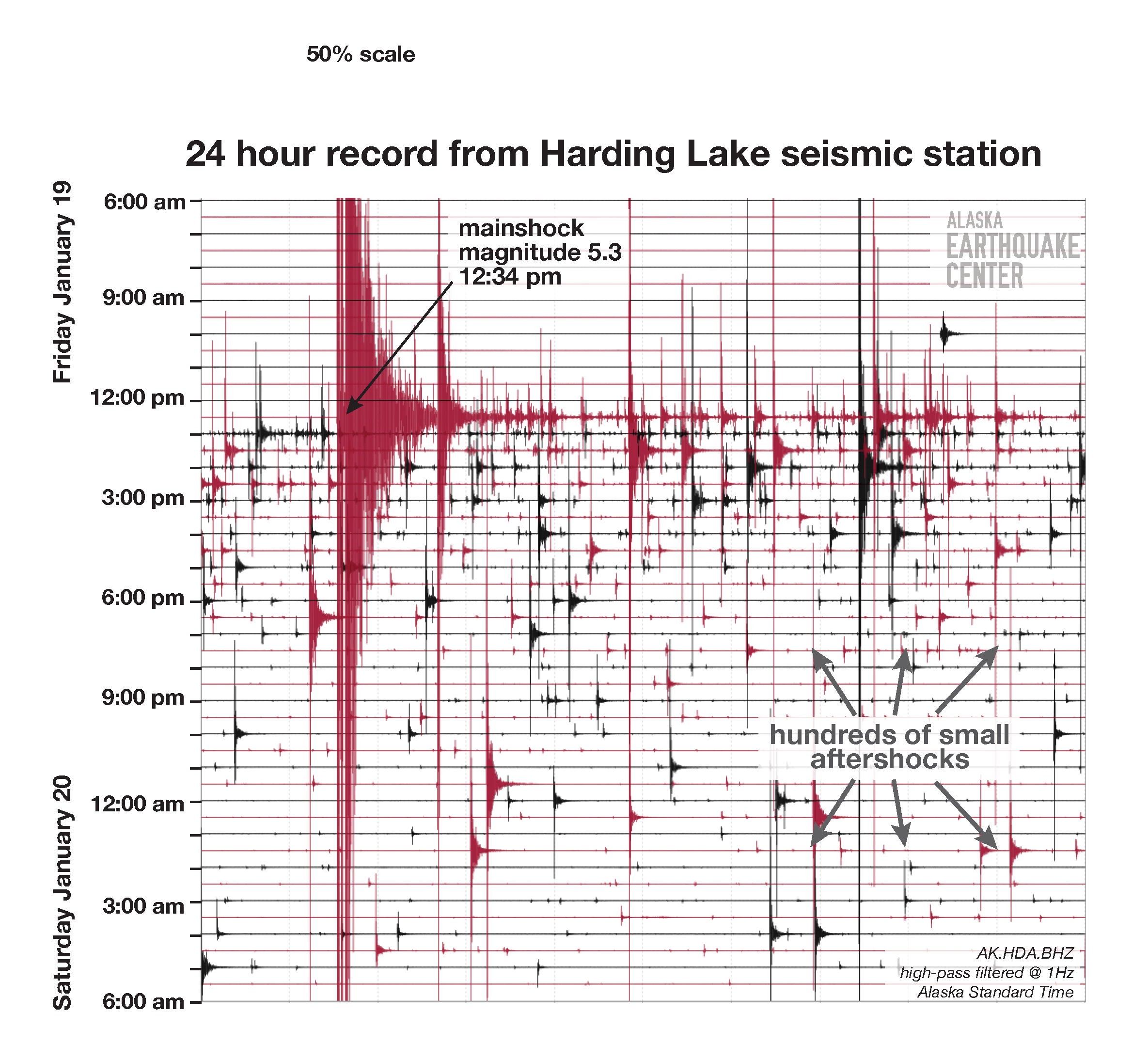

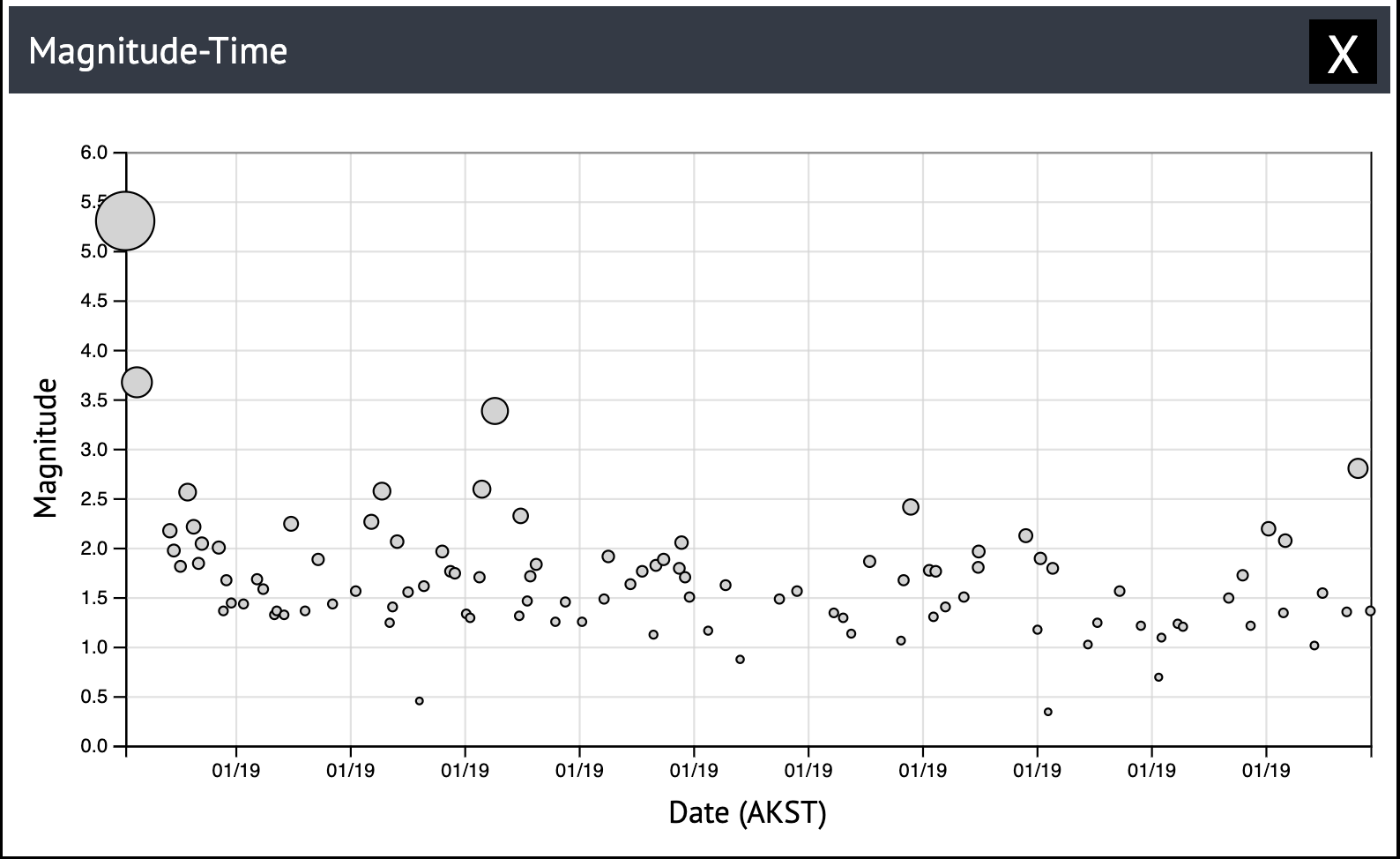

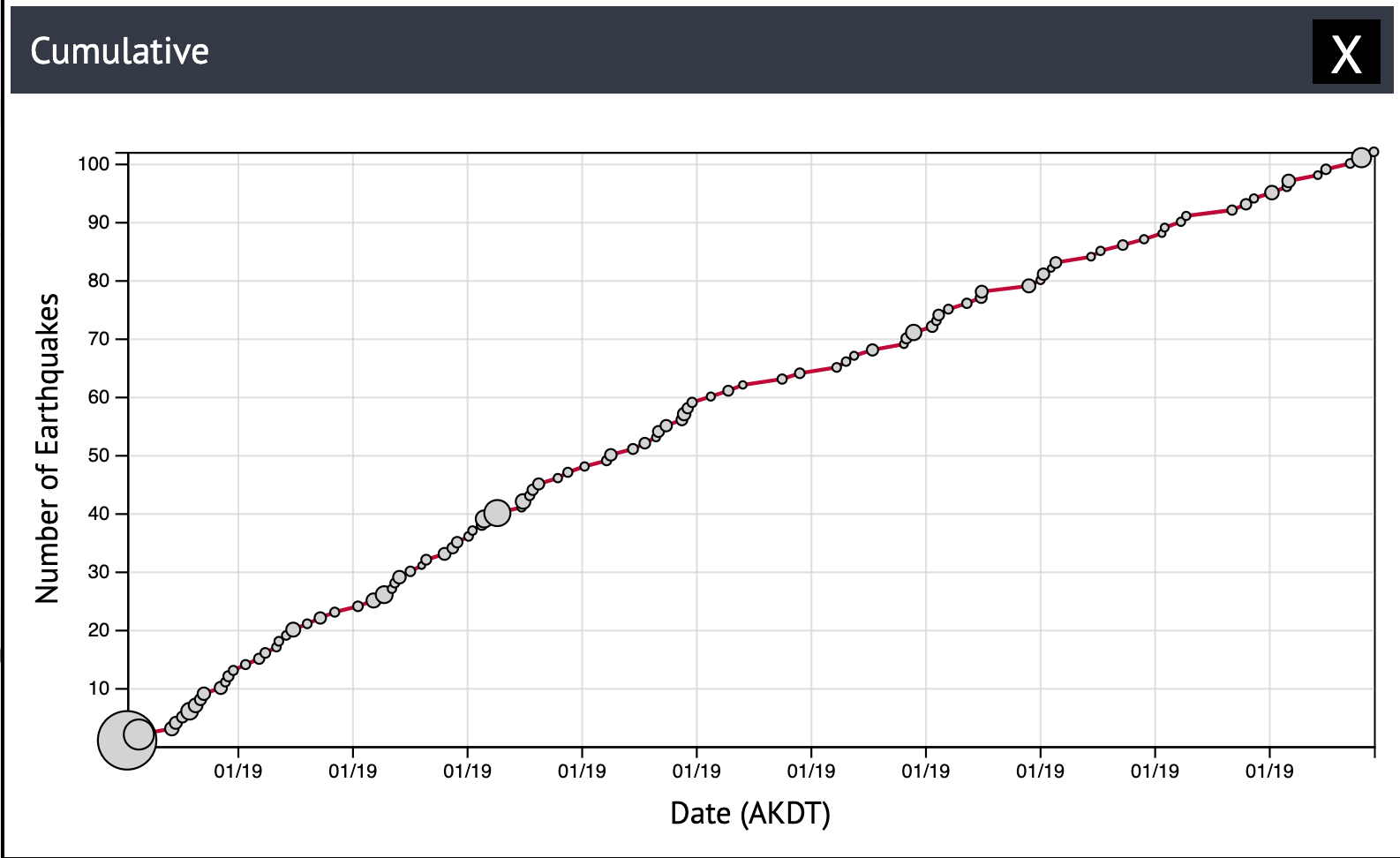

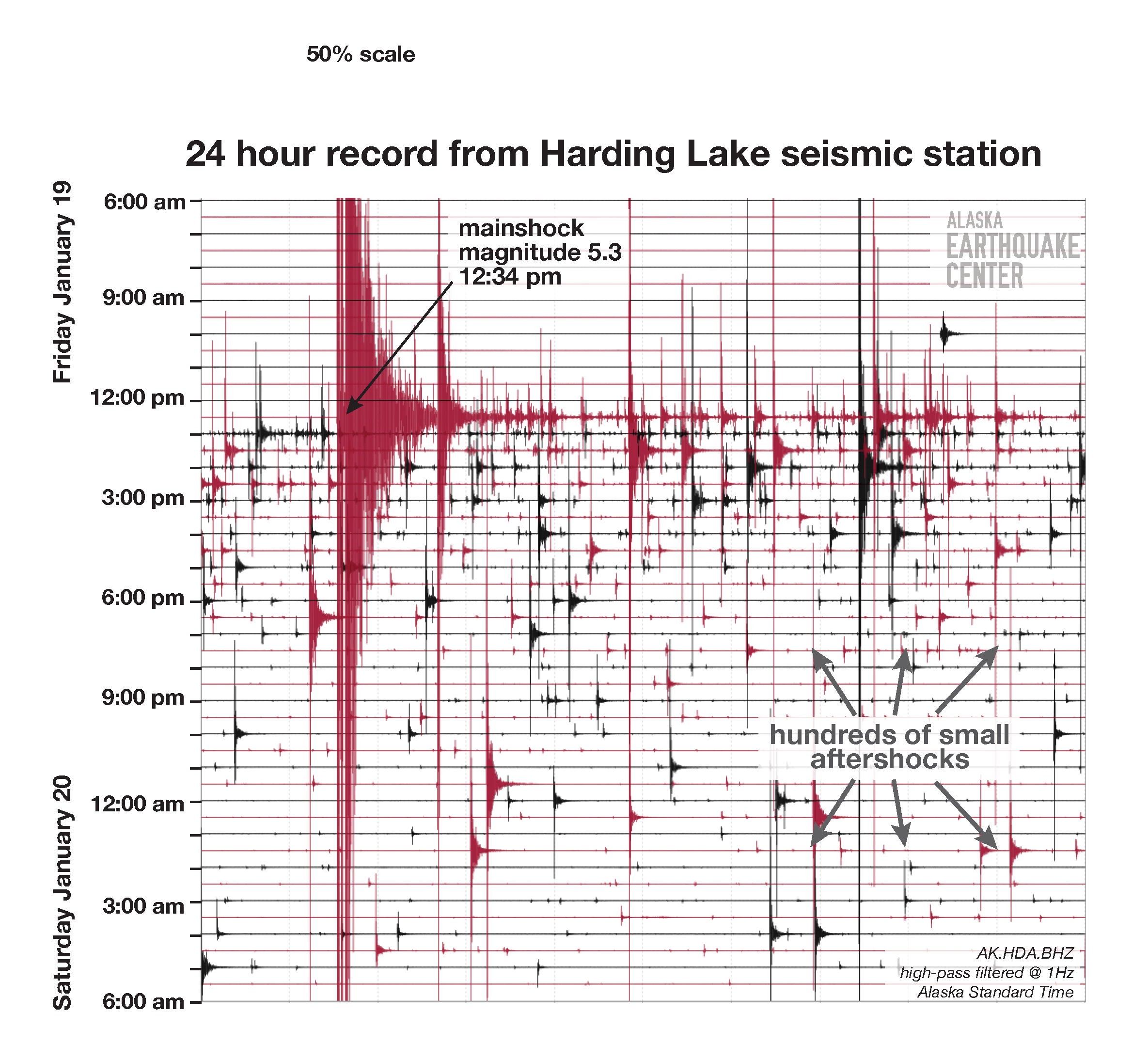

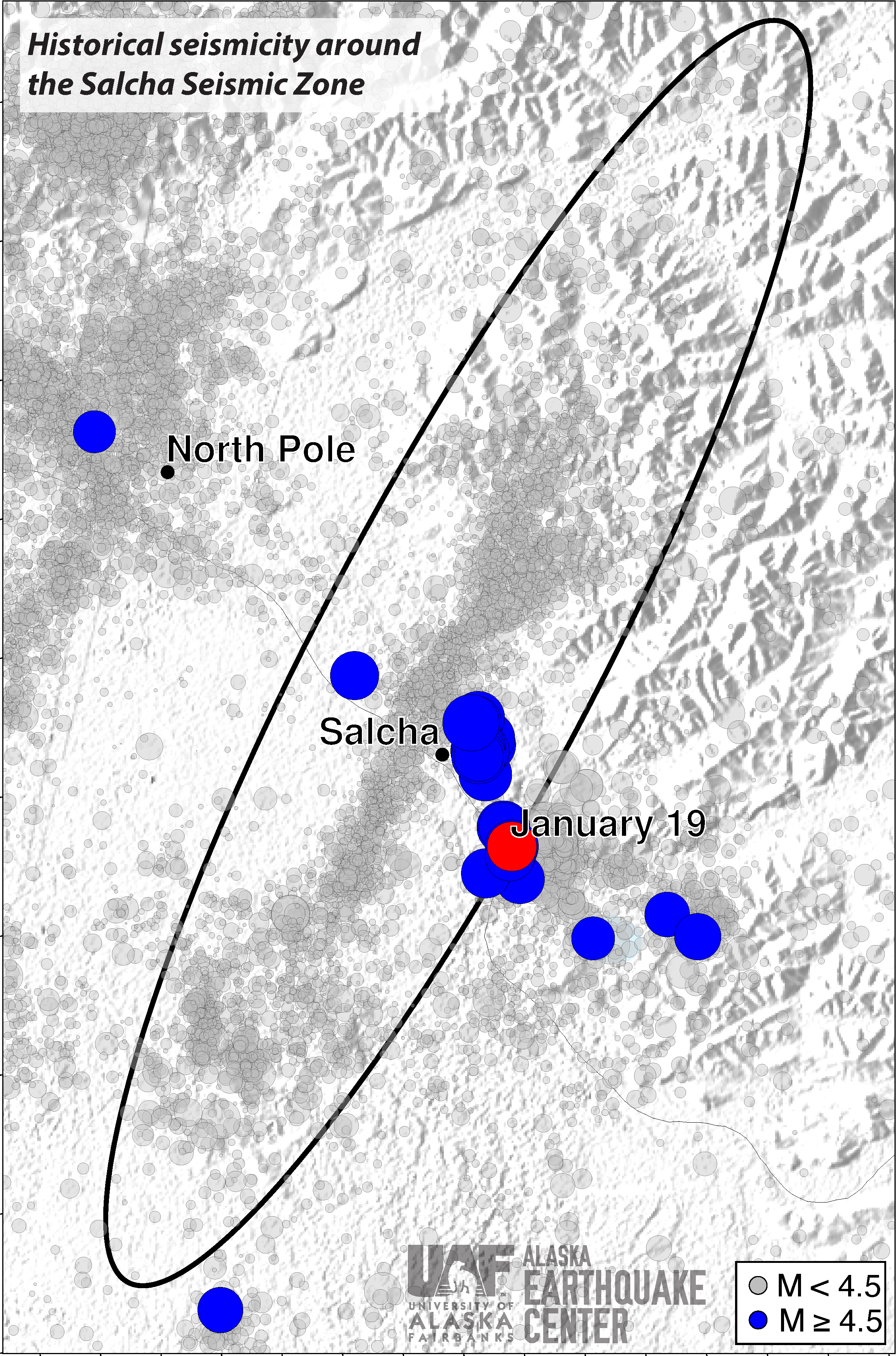

Residents who called the Alaska Earthquake Center reported near-continuous shaking for more than an hour after the mainshock (Figure 3). Indeed, more than 50 aftershocks had been recorded within three hours (Figure 4), and most were less than 10 miles (16 km) deep.

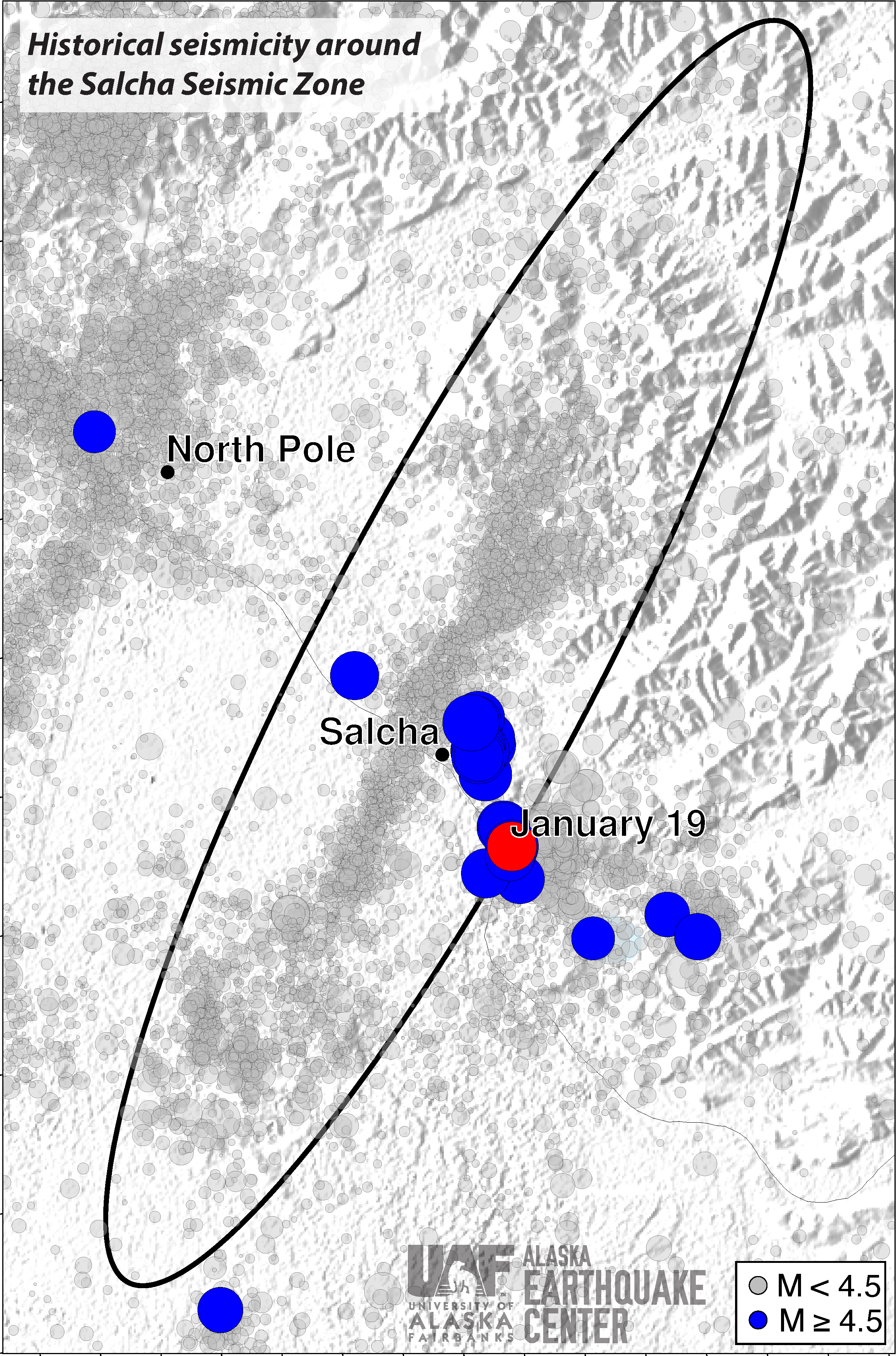

Earthquakes in this region are common, but the M5.3 event was significant, and in fact resulted in the strongest shaking felt in the area in the past decade. A seismic station near Harding Lake recorded ground shaking at 21 percent of gravity (21 %g), which is twice the shaking of the M4.9 on September 14, 2021. Another notable earthquake happened in the region just a few months prior, a M4.7 on July 22. The largest earthquake recorded in the area was a magnitude 7.1, on July 22, 1937. The University of Alaska Museum of the North ShAKe virtual exhibit contains newspaper clippings, photos, interviews and more, including those from the 1937 M7.1 Salcha earthquake.

The Salcha seismic zone is an earthquake-riddled NNE-trending lineament, which defines a fault that has no expressed surface rupture. The fault zone stretches from the northern foothills of the Alaska Range towards Salcha. This zone parallels the Fairbanks and Minto Seismic Zones to the west. Combined, these fault zones produce thousands of earthquakes each year. These broad, linear fault structures are believed to exist because the region is bordered by the Denali fault to the south and the Tintina fault to the north, causing the crustal blocks in between to rotate clockwise.

Figures 6-9 show more in-depth analysis of this earthquake.