Natalia Ruppert came to Alaska planning to stay for a semester. More than two decades later, she’s built a career at the Alaska Earthquake Center. She is currently the Senior Scientist and Project Manager, reflecting the wide range of roles she has filled at the center.

“I do project coordination when projects span different parts of the organization, since I have deeper knowledge of all the moving parts in the Earthquake Center,” says Natalia. She also helps with grant and proposal writing; handles much of the communication and coordination with Earthquake Center partners; oversees the land use permitting process; and coordinates, trains, and oversees the duty seismologists. She does “some data analysis because I still like looking at the data and finding interesting things,” so she sometimes works with the data analyst team.

The Denali Fault Earthquake

Natalia started working at the Earthquake Center as a seismologist in September 2001, a few months after finishing her Ph.D. “I continued to be involved with research related to my Ph.D. thesis and lead compilations of earthquake catalogs for the center,” she recalls.

“The Denali Fault Earthquake in 2002 was my first significant earthquake—it's still the most interesting event to me. It was the most intense ground shaking I had ever felt. So it's a personal as well as professional highlight,” Natalia says. “It was Sunday afternoon at 1 p.m., people were out and about. We were at a church potluck and I was holding my younger son, he was 18 months old at the time. I realized right away, ‘I have to get to the office,’ so after the shaking stopped I handed my son to my husband. I came to the office and stayed here very late that day.”

In Fairbanks, the magnitude 7.9 earthquake caused minor nonstructural damage, such as broken glass and pipes. It caused significant damage to the transportation systems in central Alaska.

“My first and foremost priority in the office that day, and for a few years to come, was to deal with the aftershock processing. There were so many aftershocks that we had to hire and train more data analysts to handle the workload. Also, many colleagues were reaching out to study various aspects of the event. I learned a lot more about seismology and I had several publications related to these studies within a few years.”

Starting Out in Alaska

Initially, Natalia came to Alaska for graduate school. After receiving her Bachelor’s in Geophysics from Novosibirsk State University in Russia, she participated in a month-long exchange with Stanford University. “People there said I should try grad school in the U.S., so I applied to a few programs and was accepted here at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.”

Natalia started at UAF in January 1994. “My idea was I would do one semester to see if I liked it,” Natalia recalls. “I came on a one-way ticket. I really wanted to go home during the first few months, but I couldn’t afford the return ticket. But by the time I had enough money, I was starting to like Fairbanks.” Her husband Artem, whom she met while studying at Novosibirsk State University, was accepted into the master’s program for the petroleum engineering department that summer, so Fairbanks became their new home.

Natalia’s master's thesis focused on earthquake relocations in Southcentral Alaska. She completed her master’s degree in less than two years, then accepted the offer to enter a Ph.D. program at UAF. “I had kids along the way, so my Ph.D. degree took a little longer than planned,” she says with a smile. Natalia finished in 2001, two months before her second son was born. “My Ph.D. research focused on earthquakes and tectonics in Alaska. There was an earthquake sequence in Kodiak between 1999 and 2000, with the largest events ranging in magnitudes up to 6.9 and 7.1, that caused some significant damage on the island. It started my interest in earthquake seismology in Alaska and that sequence became one of my Ph.D. research topics. Later, I expanded my research interests beyond Kodiak, to the Interior, and other parts of Alaska.”

A Career at the Earthquake Center

Since starting at the center, Natalia has had a hand in nearly every aspect at some point, from data acquisition to field network management to research. “As I learned more about the organization, I stepped into new roles: I supervised the analyst team and oversaw our real-time earthquake detection systems for many, many years. I was involved with building our first website. I was the seismic network manager for a while. This was one of my favorite roles, being able to fix malfunctioning sites and bring more data to the lab. Throughout all these years I continued to be involved with data acquisition, processing, and analysis,” says Natalia.

“I was managing field work and the field team, before and while the USArray was in early stages of development from 2012 to 2019,” Natalia said. The temporary instrument network dramatically changed the statewide coverage by installing 197 new sites across Alaska, including areas of northern and western Alaska that had never been monitored for earthquakes. When the project ended, the center acquired 96 of the USArray sites in 2019 and 2020, adding them to our permanent network.

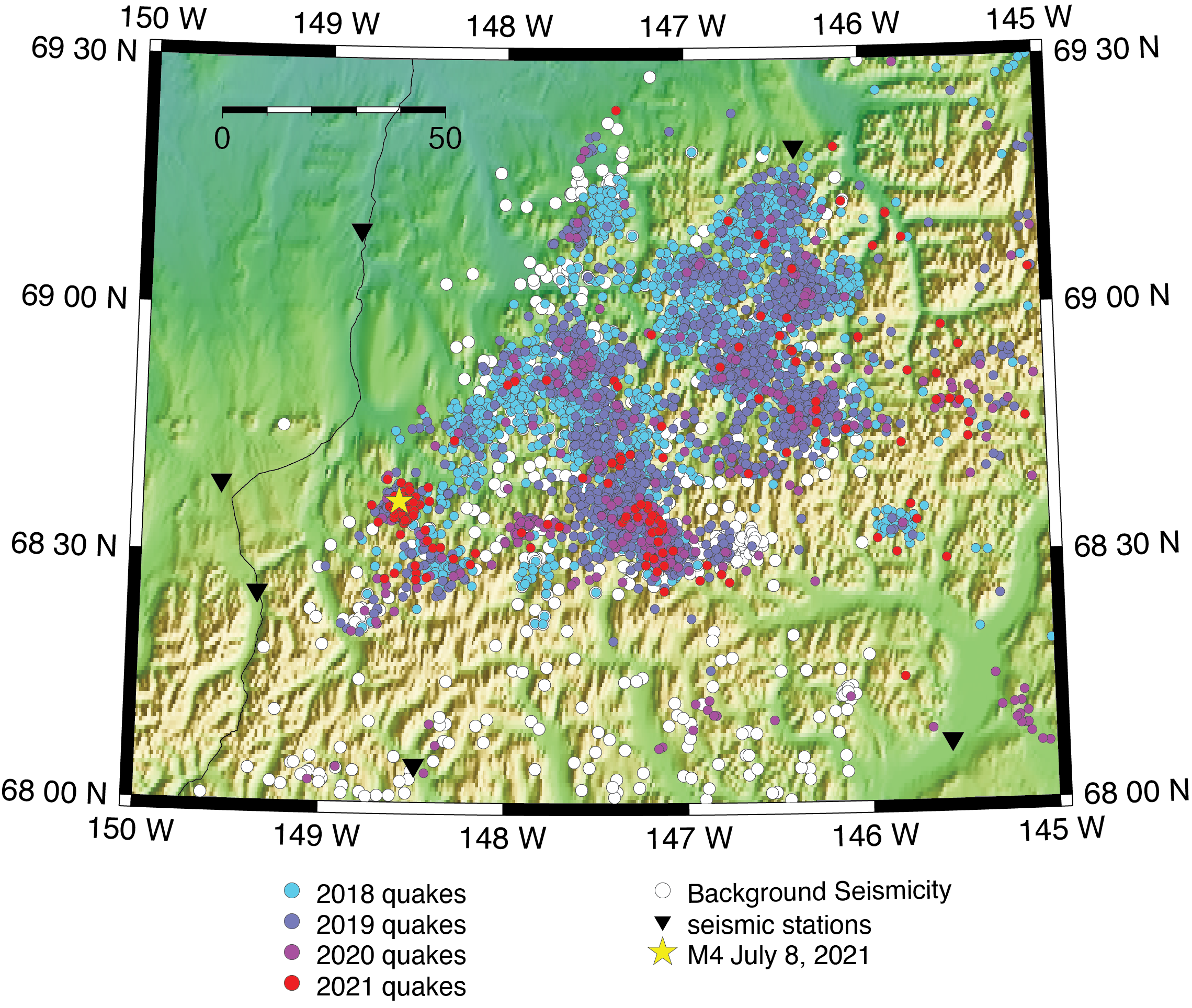

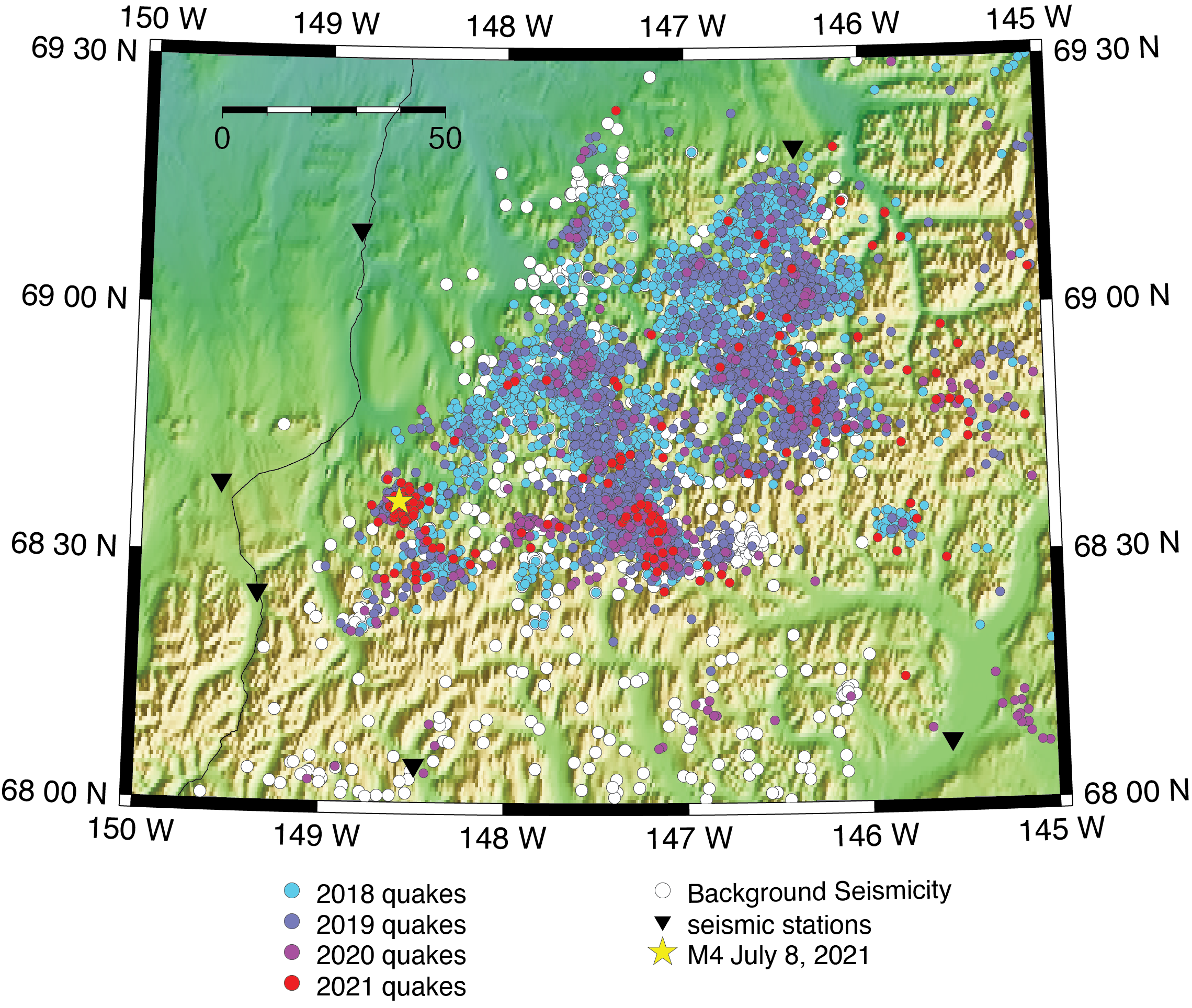

What have we learned from the USArray project? “It is basically more work!” Natalia laughs. “There are more earthquakes detected and more stations, it’s more on-the-go all the time, there is almost never down time. On the positive side, we learned more about seismicity in the northern parts of Alaska.” The amount of swarm activity there was a surprise. “I definitely didn’t think it was the norm,” Natalia says. “We knew about some swarms here and there. Now I think it’s more normal behavior than we thought for the Brooks Range (Figure 1) and the Seward Peninsula. When you don’t have stations, you only see larger earthquakes, so you don’t realize you’re missing 95% of the seismicity.”

Throughout all her roles at the Earthquake Center, one thing remains the same: “I like looking at the earthquake data. That’s where I started and it’s still my favorite part of the job,” Natalia states. “Interpreting the signals, it’s always something different every time we have some significant event because it tells us something new about Alaska’s tectonics.”