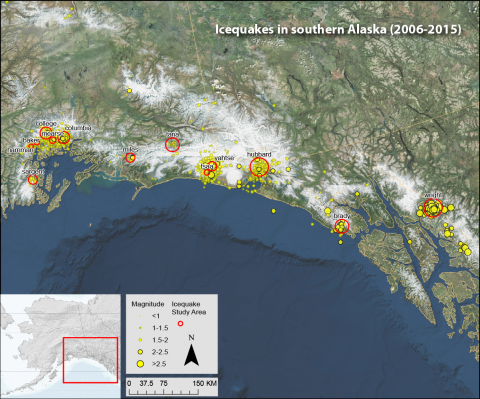

As we head into winter, seismic events generated by glaciers—so-called icequakes—have quieted down for the season. Each year, hundreds of these icequakes are large enough to be caught by our standard earthquake detection routines. Over the past decade our icequake data has grown from a scientific curiosity to a useful tool for tracking certain glaciers.

The annual cycle is unmistakable. Icequakes ramp up in April and fall off sharply in October. With a decade of data, we can now identify about a dozen glaciers with sufficiently large icequakes to create statistically meaningful records. These glaciers all fall in the coastal region from Prince William Sound to Icy Bay and Yakutat to Southeast.

Icequakes are generated by calving at the terminus of a glacier, typically where it enters the ocean. One remaining puzzle is why a few of these "noisy" glaciers are located inland where they cannot have a tidewater terminus. Tana, Wright and Brady are examples.

Recent research has demonstrated that large icequakes occur when icebergs fall intact from height into bodies of water. It turns out that these noisy inland glaciers all have lakes at their terminuses, allowing them to create calving icequakes similar to what we see in the ocean. In most cases these lakes were created by the glaciers themselves as meltwater is trapped between glaciers and their moraines. This is important because it suggests that most glaciers might have the right conditions to create large icequakes at some point in their existence. It also explains why we shouldn't immediately write off the occasional icequake in the Alaska Range or other land-locked areas.

The remote monitoring of icequakes will never be a tool amenable to all glaciers. But it now seems they do not necessarily have to end in the ocean to have a robust icequake record. A lake is more than sufficient.