From the dramatic Southeast coast to the heights of the Alaska Range and the volcanic islands of the Aleutians, earthquakes build the landscapes that drive Alaska’s rivers, glaciers, and even climate zones. Most of these earthquakes—and all major earthquakes—can be traced to the movement of tectonic plates.

The landmass beneath the Pacific Ocean is one of a few dozen tectonic plates that make up the earth’s crust. Each year, the Pacific Plate pushes a couple of inches towards Alaska, which is generally considered to be part of the North American Plate. Where these two plates meet, the dense oceanic rocks of the Pacific thrust under the more buoyant continental rocks of Alaska. This process is called subduction.

Subduction zone earthquakes follow the descent of the Pacific plate down to 200 km or more. Alaska’s largest earthquakes, exceeding magnitude 8 and even 9, occur primarily in the shallow part of the subduction zone, where the crust of the Pacific Plate sticks and slips past the overlying crust.

Examples of this type of earthquake include the 1964 magnitude 9.2 Good Friday Earthquake and the 1965 magnitude 8.7 Rat Islands Earthquake, the second and eighth largest earthquakes ever recorded worldwide.

Tectonics in Southeast Alaska are also driven by the movement of the Pacific Plate, but in a different way. As the plate inches toward the northwest, it grinds past Southeast Alaska and British Columbia. Unlike the subduction zone, these faults slip primarily in a side-to-side motion, with a different tectonic plate on each side. The earthquakes caused by this movement are shallow and occur primarily in the crust of the earth. This is a well-developed fault system that has been active for tens of millions of years and in historic times has hosted numerous earthquakes approaching magnitude 8. The 2013 magnitude 7.5 Queen Charlotte Fault Earthquake is a recent example.

Meanwhile, this northwest motion of the Pacific Plate exerts tremendous force on Alaska, compressing the land in a north-south direction and shearing or tugging southern Alaska to the west. The Alaska mainland is crosscut by numerous fault systems that accommodate this compression and shearing.

The vigor of these faults, and our knowledge of them, generally decreases toward the north, although the impact of this compression can be traced all the way into the Arctic Ocean.

The resulting seismicity is remarkable for its variety and geographic reach: events like the 2002 magnitude 7.9 Denali Fault Earthquake, and the 1958 magnitude 7.3 Huslia earthquake, as well as the highly active Minto Flats Seismic Zone, all result from this powerful compressional force.

However Alaska can also produce earthquake swarms, or a series of earthquakes that is not similar to your typical mainshock-aftershock sequence. It is still uncertain as to exactly why swarms occur, but they occur around the state and can vary in magnitude, quantity, and duration. In 2014, a swarm near Noatak rattled residents with five magnitude 5.3-5.7 earthquakes spread out over two months. In 2015, a swarm off St. George Island shook the normally quiet Pribilofs. And in 2018, a swarm in the eastern Brooks Range accounted for more than 2,000 of the year's record 55,000 earthquakes in Alaska.

HOW MANY AND HOW LARGE?

The Earthquake Center detects an earthquake every fifteen minutes, on average. In 2018, we reported an all-time high of over 54,000 earthquakes in Alaska. As our monitoring network improves, we report more earthquakes because we are able to detect smaller earthquakes across more of the state. As the EarthScope Transportable Array project added new seismic stations in previously unmonitored areas, we noticed an upward trend of detectable earthquakes from around the state.

The subduction zone produces very large earthquakes—as large as anywhere in the world—including three of the twelve largest earthquakes ever recorded. Magnitude six and seven earthquakes can nearly happen anywhere in Alaska.

We reported over 220,000 earthquakes in Alaska over the last five years. Twenty-six of those had magnitudes of 6 or greater, and three had magnitudes of at least 7. Seventy-five percent of all earthquakes in the United States with magnitudes larger than five happen in Alaska.

WHAT WE DO ABOUT EARTHQUAKES

All Alaskans live with earthquake hazards. The Alaska Earthquake Center exists to minimize our risks by understanding where earthquakes occur and why. Tracking the earthquakes that occur each day provides clues about the earthquakes that are likely in the future.

When earthquakes do occur, rapid reporting allows the public and emergency managers to assess the potential impacts. By measuring the shaking across the region, and even in buildings, we are able to assess the potential impacts and determine what type of emergency response is likely to be most effective.

The breadth of our network—with monitoring stations located in cities, villages, and critical infrastructure from Southeast to the Bering Strait—demonstrates the reach of earthquake hazards as well as our commitment to minimizing those hazards for all Alaskans.

Earthquakes Near Volcanoes

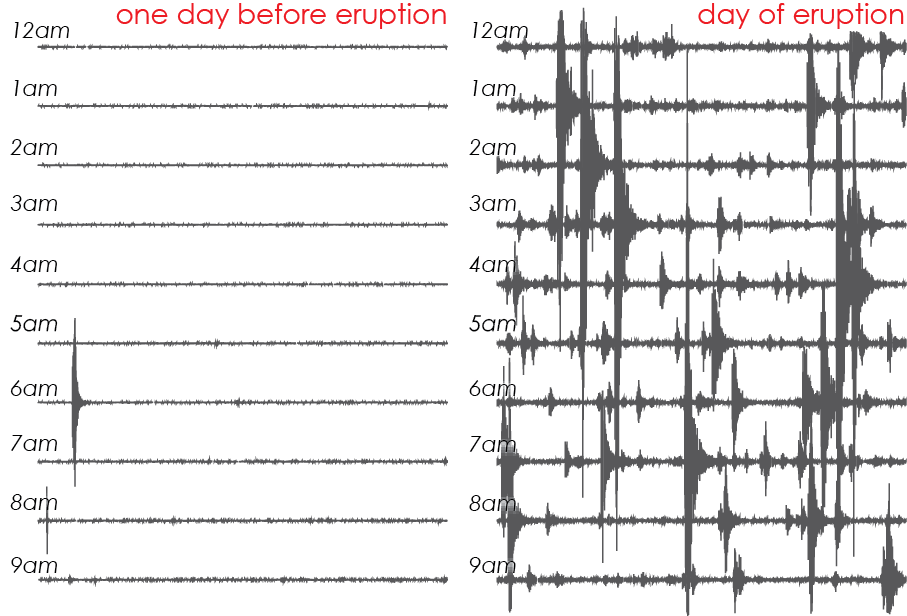

The earthquakes that occur near volcanoes are usually not damaging and are typically not even felt. They can, however, occur in very large numbers. Their occurrence can indicate changes in or near the volcano. These changes may be due to the movement of magma or gas, may result from moving ice or debris, or may simply reflect the adjustment of stresses in the surrounding region. Each of these sources produces seismograms with unique signatures that can often be used to assess the cause of the earthquake. At times, the presence of certain types of earthquakes or numerous earthquakes, accompanied by other indicators, can be indicative of forthcoming eruptions.

Ten-hour seismograms from a seismic station on Atka Island on August 6 & 7, 2008. The sudden appearance of numerous earthquakes was an early sign of an eruption that began later in the day on August 7. Not all swarms of earthquakes indicate eruptions; but nearly all eruptions are preceded by vigorous seismic activity.

Subduction zones, where most active volcanoes are found, also generate high rates of earthquakes that are not volcanic. Though volcanic activity causes only a small proportion of Alaska's earthquakes, these earthquakes often warrant more detailed analysis.

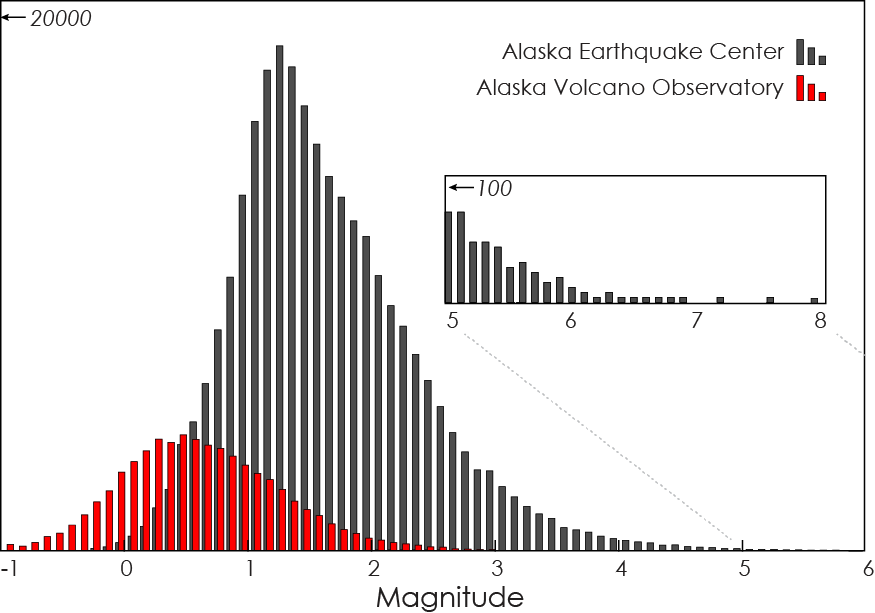

Identifying and characterizing earthquakes associated with volcanic processes requires its own tailored workflow. To achieve this, the Alaska Earthquake Center partners with the Alaska Volcano Observatory to track all notable seismic activity in the state. The Earthquake Center addresses large earthquakes and their societal impacts, while the Volcano Observatory focuses on the smaller earthquakes that can occur in large numbers near volcanoes.

Seismic data is only one tool for monitoring volcanoes. The Volcano Observatory combines these with other observations, including geology, satellite imagery, ground deformation and local observations to assess volcano hazards.

Contributions to the Alaska earthquake catalog over a decade. The bulk of the Alaska Earthquake Center catalog is above magnitude 1.5. The Alaska Volcano Observatory plays an important role in tracking the smaller earthquakes common in volcanic areas.

For information about recent volcano seismicity visit Recent Volcano Seismicity or the Alaska Volcano Observatory website.