St. Lawrence Island lies in the Bering Sea, just south of the Bering Strait, and is one of the most remote places in North America. The island is only 45 miles (72 km) from Russia—you can clearly see the Russian coastline from the village shore. Two Yupik villages, Gambell and Savoonga, lie along its northern coast.

St. Lawrence Island plays a key role in the Alaska Earthquake Center’s seismic network because station GAMB is one of few in position to monitor earthquakes in the northern Bering Sea, as well as in the strait between Russia and the Seward Peninsula. For example, as the nearest seismic station for two April 30, 2010 earthquakes, GAMB was critical for locating the magnitude 6.5 mainshock followed by a M6.3 aftershock five minutes later.

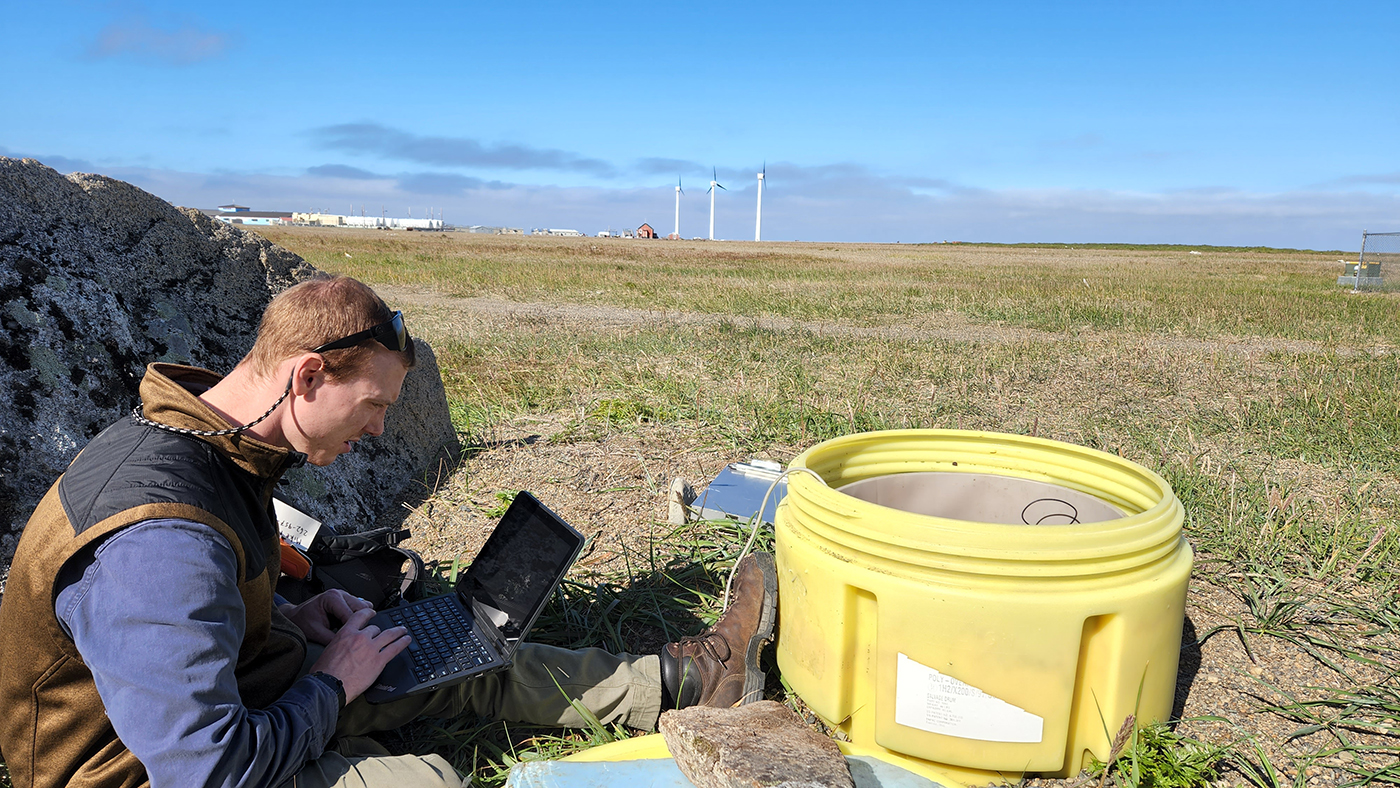

As a field engineer, getting the call to travel to a remote location is my dream. Field work has its downsides—being away from home for long periods of time, working long hours with fewer resources on-site than needed, weather that’s often too hot, freezing cold, or raining sideways, and something always either trying to bite or sting you. For me, though, I relish the freedom and experiences. I have been able to see parts of the country most people don’t get to see, and meet people I would never have had the opportunity to meet otherwise. Because of field work, I have been fortunate enough to travel to many of the places I read and dreamed about as a kid. So, when my coworker Michael Place and I were called to repair an antenna and a telemetry radio in Gambell, I was excited.

Our work in Gambell was straightforward—an antenna mast at the village’s water pump house was broken, and the radio at the school wasn’t working properly. After landing in Gambell we checked in to the Sivuqaq Lodge. Shortly after, a BBC film crew arrived. They were there to film the Life Below Zero: First Alaskans TV show. Some of the film crew had been there earlier filming for the BBC Earth program, Frozen Planet II. You know you’re in an incredible place when you’re working around Planet Earth film crews.

We scoped out the work that needed to be done at the Earthquake Center sites. In true field-work fashion, nothing was as simple as expected. As an example, the roads in Gambell are made from foot-deep loose pea gravel gathered from the beach, which makes walking around carrying tools and equipment very tiring. (It’s a great calf workout, though.) It didn’t take long to figure out why the radio at the school wasn’t working properly—the antenna had been ripped off the building. The good news was that we found it on the floor in the school’s cafeteria. Fixing the pump house radio mast took only a few minutes. By this time, it was getting late and we called it a day. I quickly ate dinner and set out to explore the village and ocean.

Not a lot of people visit Gambell, and many of the residents were curious about what I was doing there. As I sat on the beach, several people came to talk to me. I heard many incredible stories about walrus and whale hunting in the Bering Sea and what it’s like to live on the island. Several villages in Alaska hunt whales, and Gambell is known as one of the most elite. I was told a few stories about whale hunts, including some tense encounters while hunting near Russia during the Cold War.

As I listened to people talk about hunting and living on the island, a group of at least a hundred gray whales swam within a couple hundred yards of the shore. As I looked farther out, I noticed that there were whales breaching everywhere. I asked the people near me if they would go hunt the whales, and they said that they don’t hunt gray whales or killer whales because they don’t taste good. They only hunt bowhead and beluga whales in the springtime. Another village elder explained that they used to have to carry their walrus skin boats out on the sea ice over a mile from the village during the spring hunt. Now they use motorized boats, and the sea ice is gone by the time the whales migrate through. The boats must leave from the beach, which is more dangerous due to the high surf in the frigid water.

The island is also home to nearly 3 million nesting seabirds in the summer months. Seabird eggs are an important traditional food for residents. Gambell is also a top destination for birders. While I was on the beach talking to people and watching the whales swim by, tens of thousands of seabirds flew overhead, heading out to sea to feed. I sat on the beach from about 9 pm until after midnight, and the line of whales and seabirds going by never slowed.

The next day, it didn’t take long to put up a new antenna at the school and make sure everything was working properly again. By midafternoon we were done working and headed back to the lodge. A village elder stopped by the lodge and offered us a tour around Gambell. We jumped on her four-wheeler, and she showed us the remnants of old homes made from whale jaw bones and walrus skins. She took us to the “bone yard” and showed us the whale and walrus skulls left from decades of hunting, and told us what it was like growing up on the island. After the tour, more people stopped by to show us some of their walrus ivory carvings, which Gambell is known for.

That evening we went back to the beach to see if the whales and seabirds would return. Sure enough, like clockwork they were there, but a storm was closing in and all the action was farther from the shore this time. We had amazingly good weather for the trip, but it is not uncommon for planes to be unable to reach Gambell for a week due to bad weather. We decided not to push our luck and left the next day.

This trip was about more than just repairing a seismic monitoring station in a remote part of Alaska. Meeting the people, learning about their lives, and telling them about what the equipment does connects us to unique Alaska communities like Gambell.