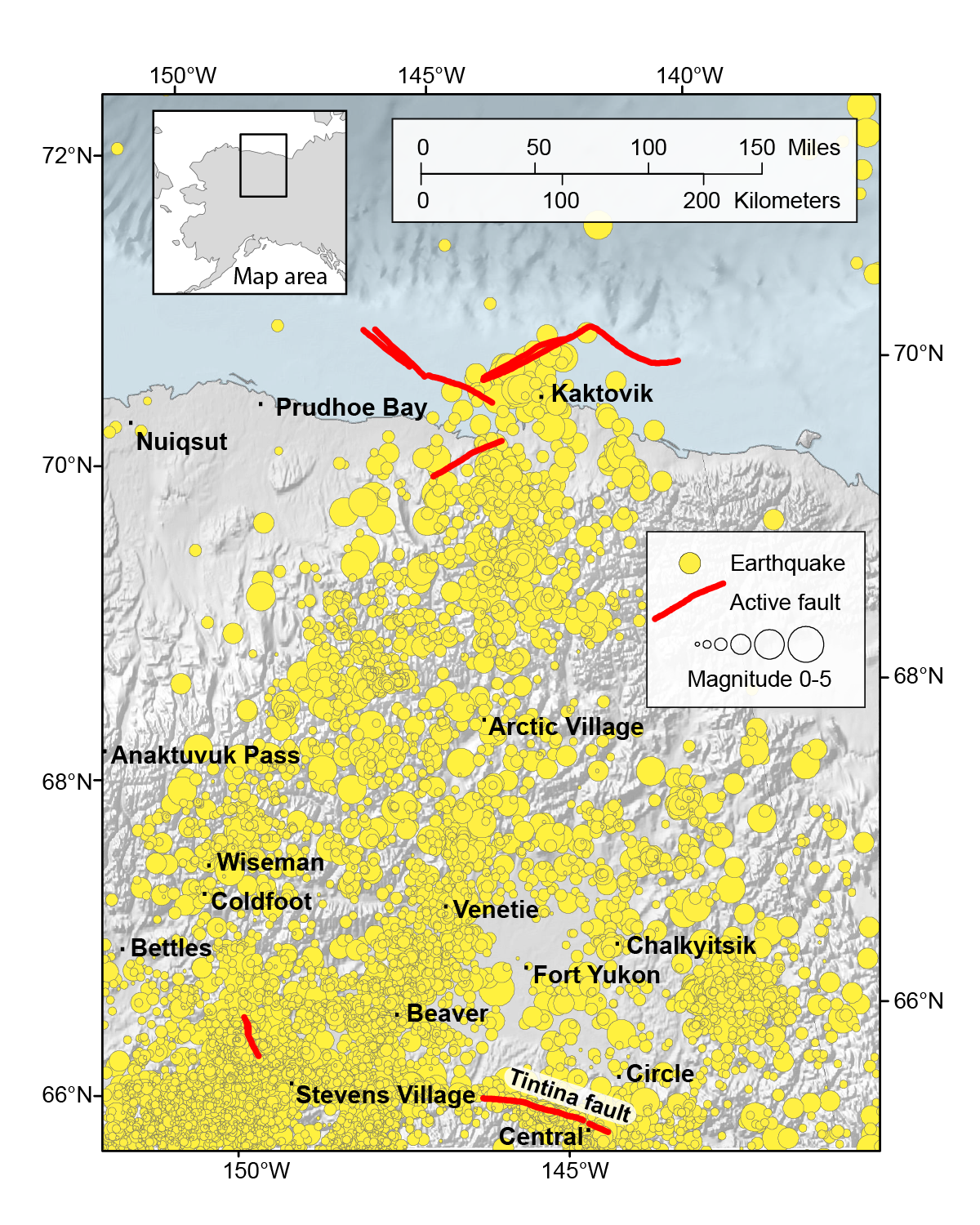

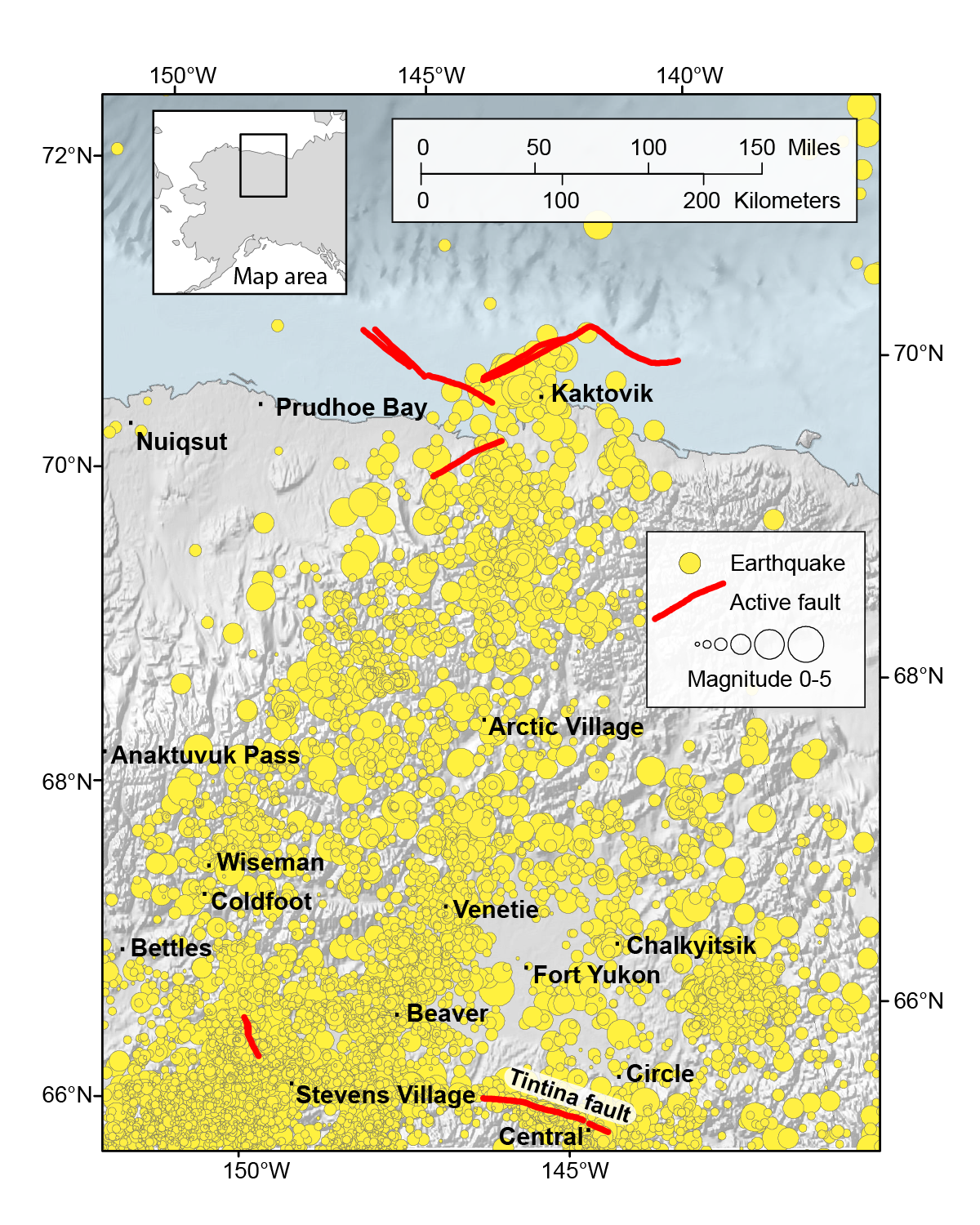

With only a handful of known active faults across northeast Alaska, you might not expect much in the way of earthquake activity. You’d be mistaken. Earthquakes have been recorded in this lonely corner of the state for decades, ever since monitoring began in the early 1970s. The Alaska Earthquake Center detects a magnitude 5 earthquake there every 8 years, along with many hundreds more smaller earthquakes that are too small to be felt. The running total as of January 1, 2018 was 4,444.

So where are the faults responsible for all this earthquake activity? To find out, we usually look to the State of Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Survey’s impressive interactive map of the state’s active faults. This map was many decades in the making, compiled by geologists who spend months in the field each summer looking for evidence of active faults and mapping them in excruciating detail. In most parts of the state, the earthquakes detected by the Alaska Earthquake Center cluster around faults that appear on the map - as we would expect. It makes sense. You need a fault to rupture to get an earthquake.

Yet the map shows only a handful of offshore faults along the North Slope and then a great, blank expanse until the Tintina fault that runs through the village of Central, 300 miles to the south. This absence of mapped faults is entirely due to the wild, remote, and largely uninhabited nature of the country. It remains under-studied thanks to the logistical challenges of working there. Until this area is studied and mapped, we have to rely on the earthquake record for clues about how the ground is moving.

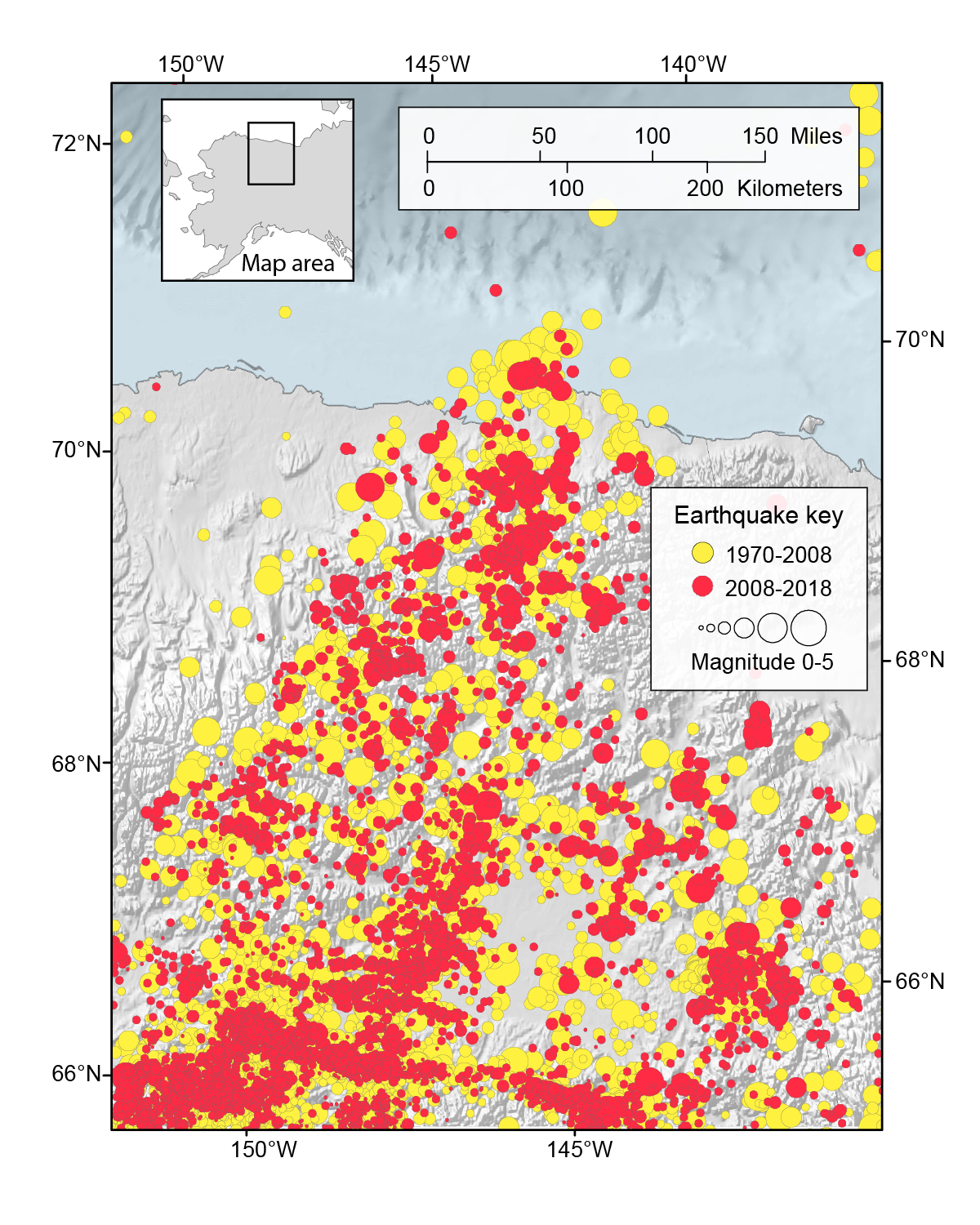

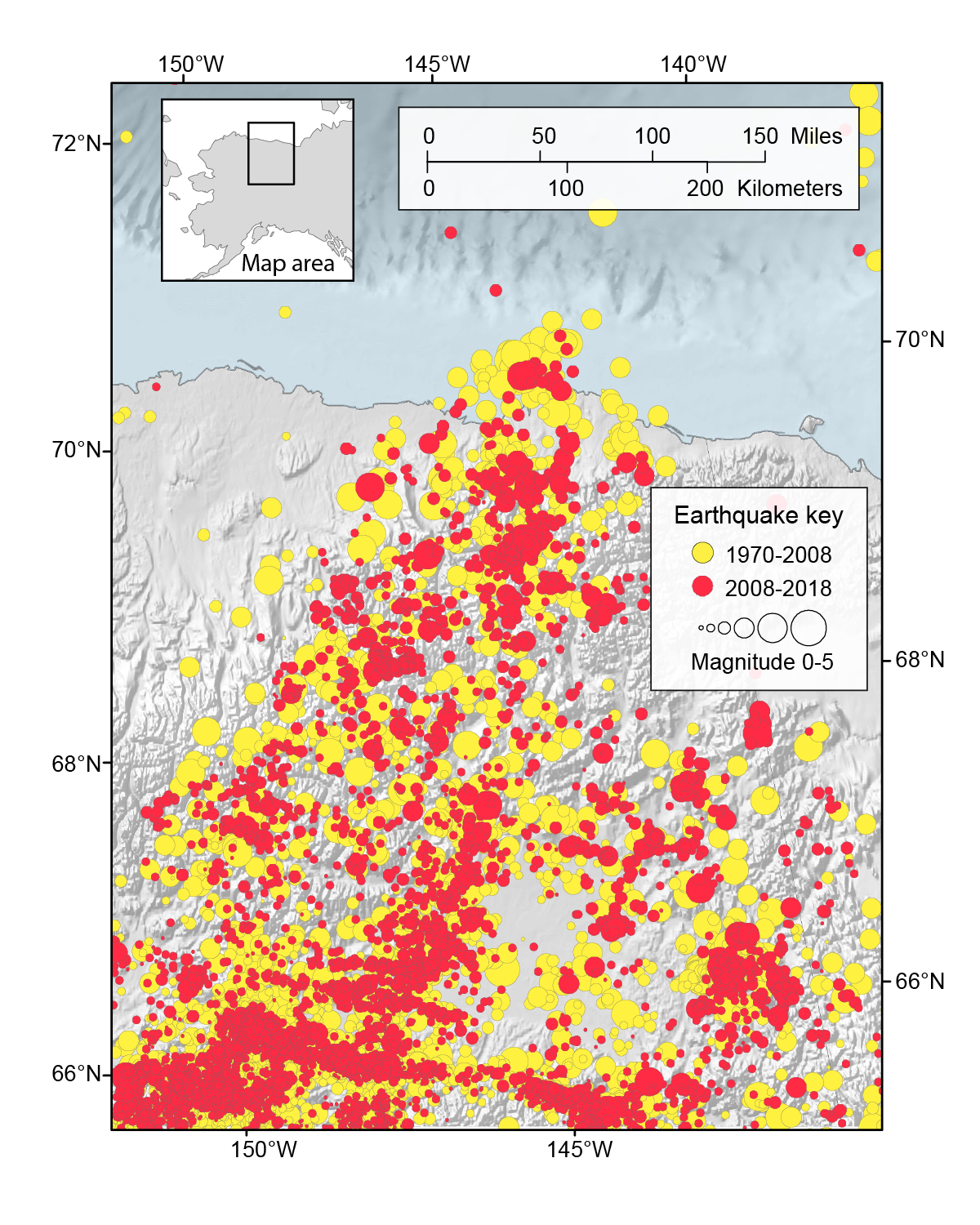

It turns out that the earthquake record is proving to be more and more insightful thanks to recent improvements in earthquake monitoring. Up until 2008, there were only three seismometers that were recording earthquakes in northeast Alaska. These seismometers were able to pick up larger earthquakes, but they were spaced too far apart from each other to be able to detect the smaller earthquakes that often get called ‘microseismicity’. Since 2008, 35 new seismometers have been added in northeast Alaska, largely thanks to the ongoing USArray project. They are spaced closely enough together that the microseismicity has lit up.

Microseismicity - loosely defined as earthquakes below magnitude 2 - helps us to find faults. By coloring the earthquakes that happened after 2008 in red, we can more easily pick out where the microseismicity is focused. In this version of the earthquake map you can see that the Tintina fault shows up as a line of earthquakes, and that it actually seems to extend much further west than the mapped fault suggests. This is probably because the western part of the fault doesn’t quite reach the surface, so the geologists were not able to track it there. You can also see a number of other lines of microseismicity pop out of the map (depending somewhat on how hard you squint at it). This is where we think many of the unmapped faults can be found.

The geologists will get the final say on where exactly these ‘new’ faults are, once they have finished their mapping studies and figured out how the rocks are related to each other. But I know there will be some seismologists who will be secretly thinking “yeah, but we saw them first”.