Not only do our remote seismic stations need to survive temperatures far below zero, heavy snows, ice, winds, rains, lightning strikes, and warm, muddy summer months, our stations must also withstand abuse from all variety of curious, furry Alaska residents. Our seismic station on Baldy Mountain (BAL), about 20 miles from McCarthy across the Chitina River, has a history of being damaged by bears (fig. 1). So, when the site went offline at the end of summer in 2017, Alaska Earthquake Center’s seismic network engineer Scott Dalton states, “we knew we were likely looking at bear damage, but we didn’t know exactly what kind of bear damage.”

When a site goes offline, if there is a history of bear damage, especially if it is in a brushy location, bears are one of the first things we think about. Conversely, there are sites like Bagley (BAGL)—another site the team visited on this trip—which looks out on the massive 3,000-foot-deep Bagley Icefield in Wrangel-St. Elias National Park. Dalton says there are no bears within “20 miles of that site… just because of where it is. A bear would have to cross a giant glacier to get there and there are just no enticements, there is no reason for him to be there. No food. So, when something goes wrong at [a site like] BAGL, I don’t immediately think that it must be a bear.”

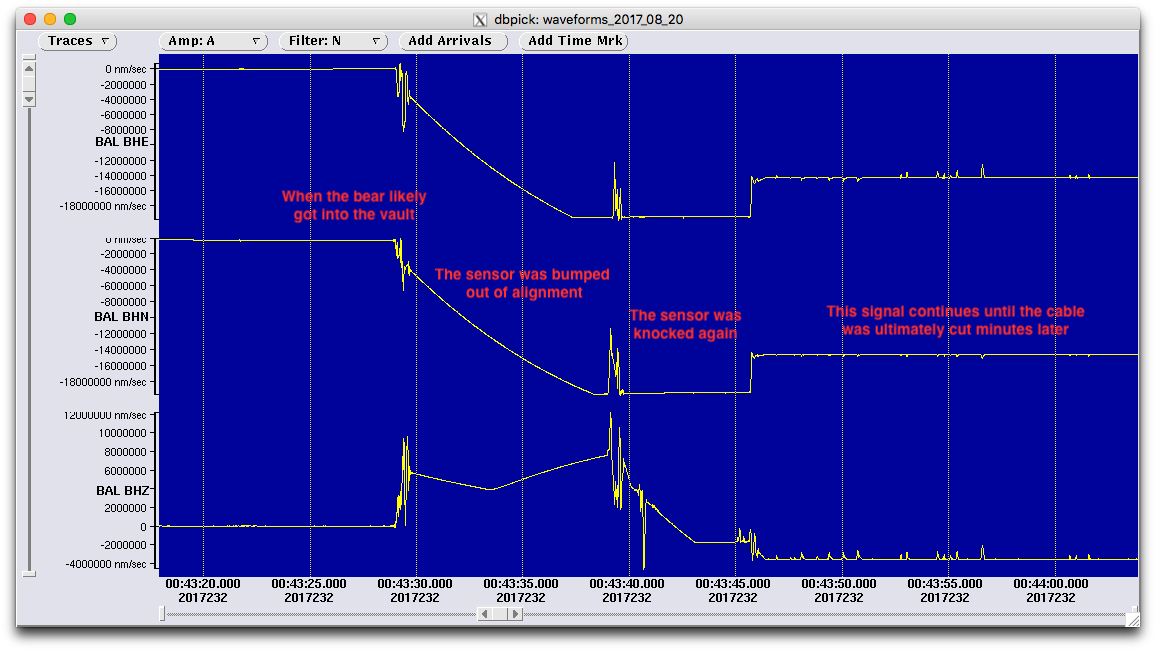

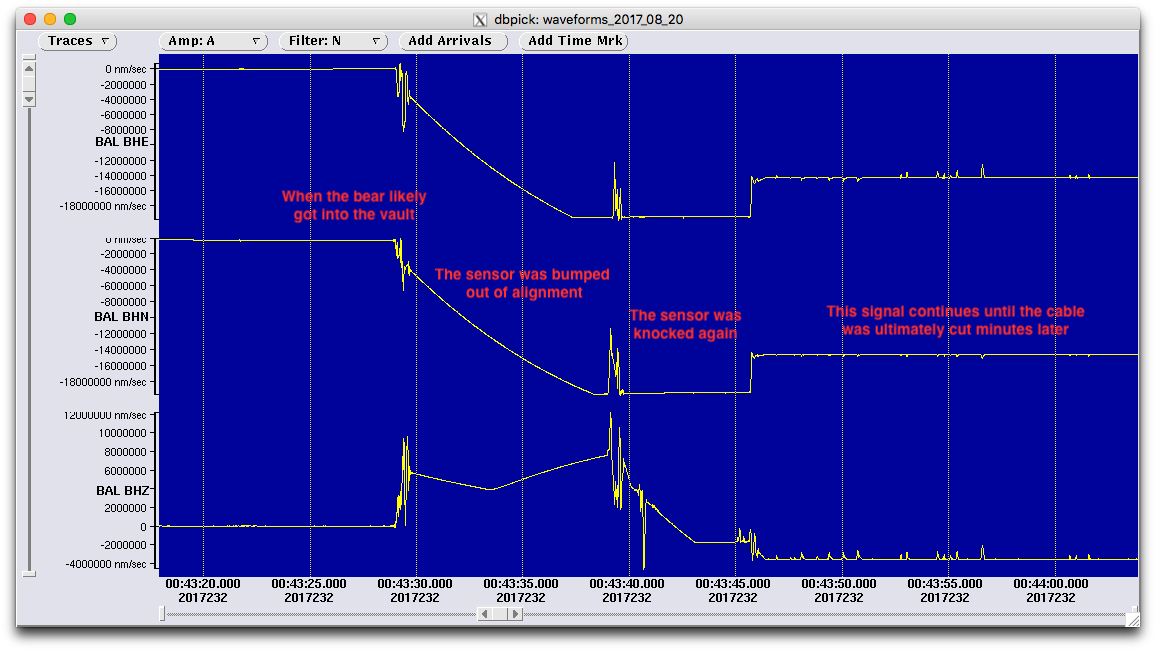

Dalton says, “it is rare for a bear to get inside our equipment enclosure, the fiberglass huts.” He goes on to explain that the huts contain batteries and communication equipment, while the yellow vaults contain seismic measuring instrumentation and often a datalogger. Dalton clarifies “if we can communicate with the site, the power system is working. But, if we can’t talk to the seismic equipment this tells us the problem is outside of our hut.” In the case of BAL, technicians predicted that something had chewed or severed a cable between the hut and the vault. Dalton laughs, “turns out it was the whole vault that had been torn apart.” Figure 2 shows the bear-created waveforms recorded at BAL just before the site went offline in 2017.

When the site went offline our technicians at the earthquake center could tell, using remote diagnostics, that everything in the hut was still working and everything in the vault was not. During the winter months our field technicians began coordinating logistics and readying gear: tools, shovels, spare equipment such as seismometers, dataloggers, spools of cable, conduit, and solar panels. The team arrived in McCarthy, Alaska their home base for the week, prepared to service BAL and three other remote seismic sensing stations between June 19 and 23, 2018.

Dalton recalls their arrival at the site: “we could see from the air, the lid for the vault was gone [and] there was lots of foam debris everywhere. The bear was still there, but we scared him off with the helicopter.” The helicopter pilot, armed with a pistol, kept an eye on the black bear while our field techs got a closer look at the work they had ahead of them to bring the station back online. The bear didn’t go far; he continued to watch our technicians work from a nearby hill.

The seismic vault, an 80-gallon overpack drum set in a concrete slab, was flooded. The bear had figured out how to unscrew the lid, ripped the cables out of the buried conduit and tore sensitive instruments out of the vault. Dalton said, “it looked like it spent a few weeks or months chewing on the foam insulation.” Bits of foam were strewn in a wide radius around the site (figure 2).

After bailing water out of the swamped vault and cleaning up the pulverized insulation, the team reinstalled new instruments into an old vault, installed in 1973 but disused since 2010. Our technicians dug new trenches and laid new cables in conduit buried deep underground to reconnect all of the components and circumvent future animal damage. They replaced solar panels and installed a new seismometer and a datalogger—an expensive piece of high-tech equipment the bear carried off somewhere. All the while, the bear watched.

Our team’s efforts paid off. BAL is once again an active part of our vast network of seismic monitoring stations feeding information to the Alaska Earthquake Center in Fairbanks—for now. Well, at least until our bear friend gets another craving for delicious closed cell foam insulation.