In August 2025, the field team reported good news a decade in the making: the Deception Hills (DCPH) seismic station is back online! DCPH faced nearly all of the challenges Alaska throws at our seismic network—bear damage, lightning strikes, and power and communications system problems—that led to years offline for this important station in the coastal hills southeast of Yakutat.

“When that station is out, we have one of the largest land-based gaps in our network,” said Heather McFarlin, the Alaska Earthquake Center seismic data manager. “You can get up to magnitude 8 earthquakes in that area, so having DCPH there really helps determine an accurate earthquake magnitude and location.” Our on-duty seismologists use data from at least 6 stations in order to calculate the best location and magnitude.

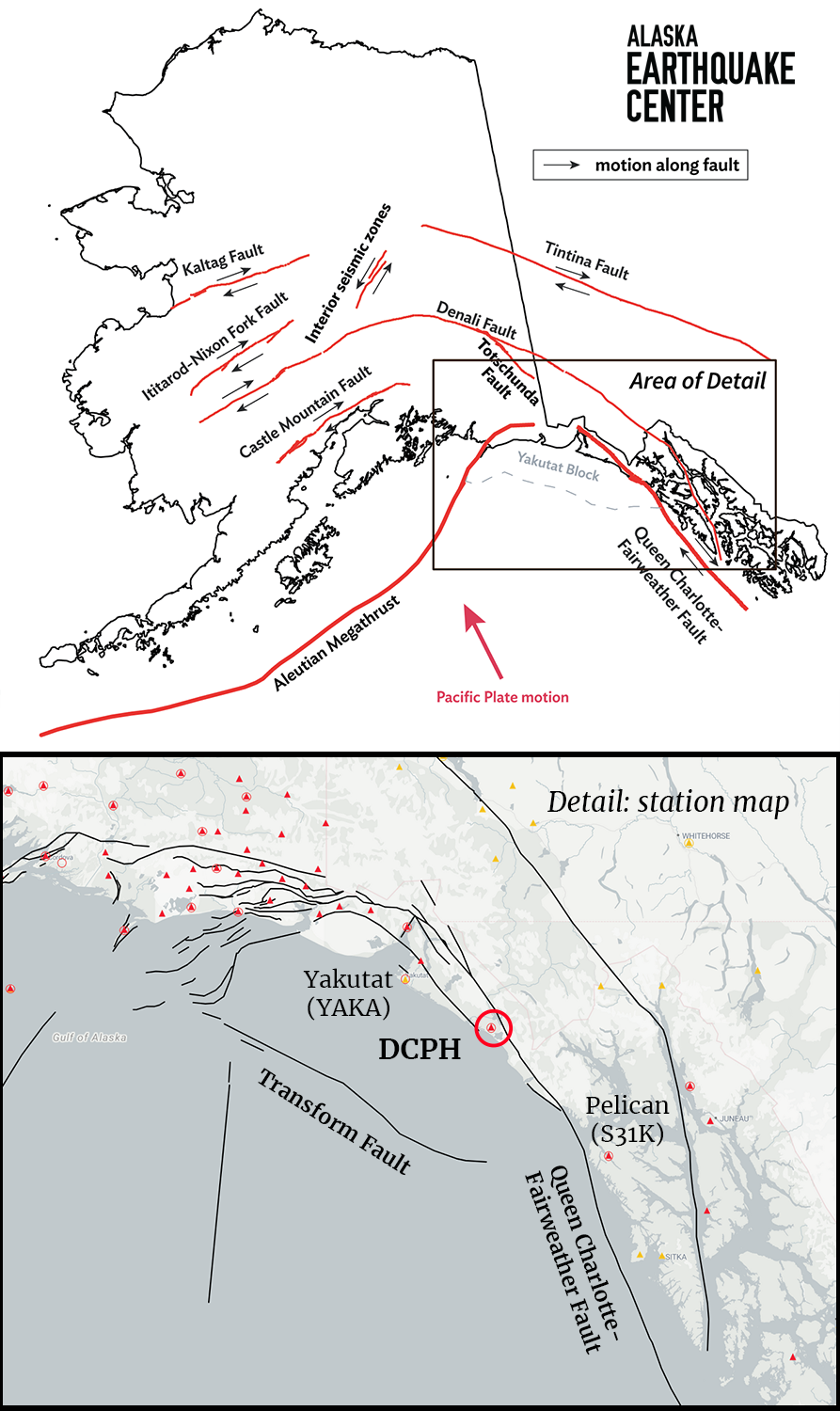

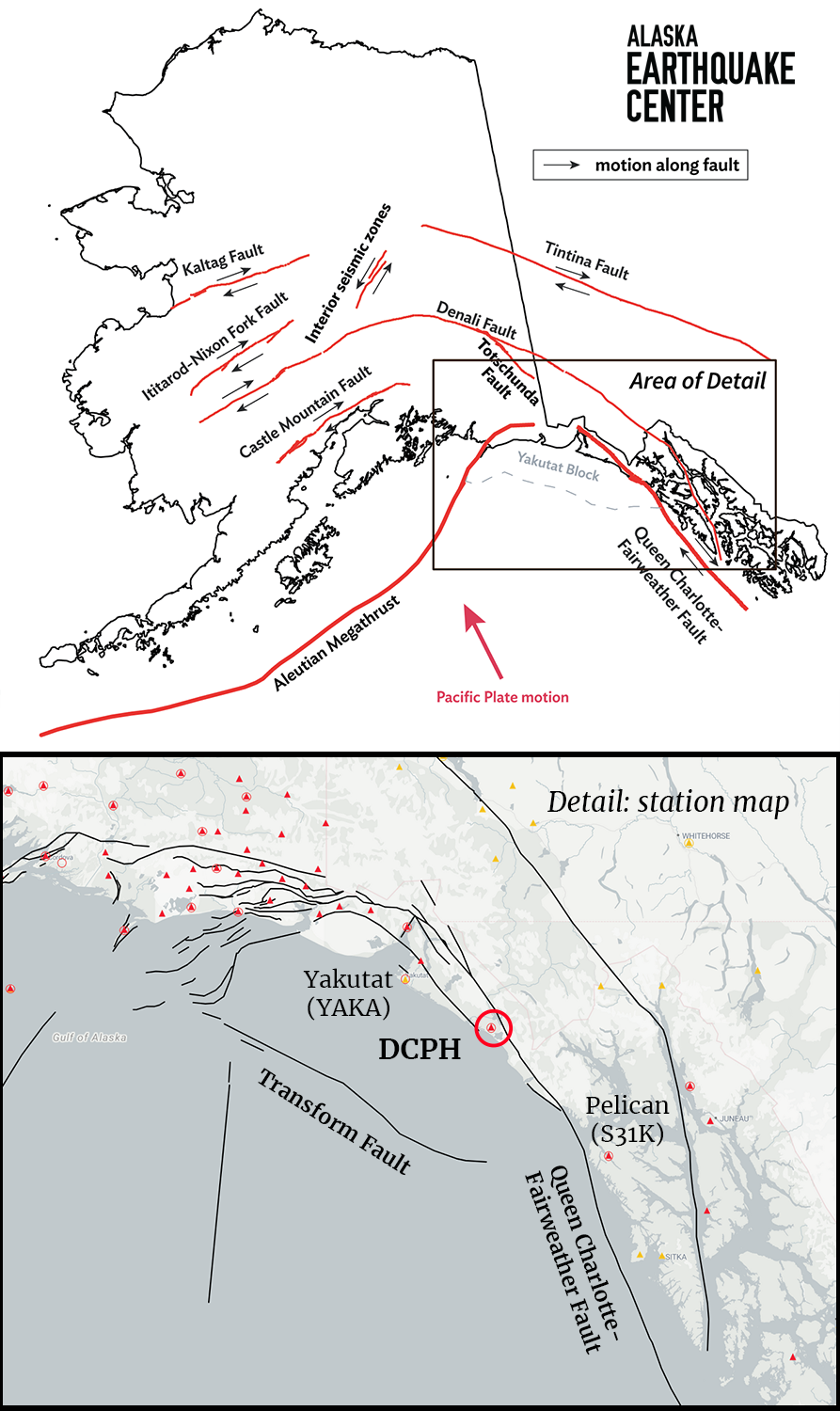

This station, the only one between Yakutat and Pelican, could be a critical spot in the future as we work toward an earthquake early warning system for Alaska. In this area, there is a history of large earthquakes from both onshore strike-slip faults and the offshore subduction zone. “DCPH practically sits on the Fairweather Fault, so it’s a pivotal station for monitoring earthquakes there and in the Yakutat transition area,” said Michael West, director of the Earthquake Center (Figure 1). The station also provides data to the National Tsunami Warning Center, which relies on fast and accurate magnitude and location determinations to issue tsunami warnings in the wake of large offshore earthquakes.

A complicated history

“DCPH is 100% rooted in tsunami response. That’s its origin story,” said West. DCPH was installed in 2002 as part of the Consolidated Reporting of Earthquakes and Tsunamis (CREST) project, funded by NOAA and the U.S. Geological Survey to establish well-spaced coastal seismic stations for tsunami monitoring.

Perched near the top of a ridge, DCPH is in a challenging location. Often fogged in, even if weather is clear at sea level, the area is also prone to ocean storms, and DCPH has been damaged by lightning a few times, according to the field team. And wildlife can be problematic, with bears causing damage several times by digging up and chewing on cables.

DCPH operated well, with occasional outages from weather or wildlife, for a dozen years. This remote station started out with a hut setup (Figure 2), with solar panels to provide power to the seismic instruments. In 2014, the U.S. Coast Guard began construction on a remote search and rescue communications facility near DCPH. This provided a good opportunity for a partnership, like we have with many agencies, towns, companies, and individuals across the state. We could link our seismic station to the Coast Guard station’s reliable power source and communication resources to transmit data to Yakutat.

In light of the agreement, the Earthquake Center removed the original hut in 2014, and the Coast Guard moved the seismic vault to minimize noise in the seismic data from the power generator’s vibrations (Figures 3, 4). This introduced a new challenge: the Coast Guard station and the seismic instruments wound up about 375 feet away from each other. We generally use ethernet cable to connect the seismometer to the communications equipment. However, after about 330 feet, the signal traveling the copper wires of an ethernet cable may become unreliable, so it wasn’t clear how stable the data flow would be. Not only did the field team have to lay out the cable, but the whole length had to be painstakingly threaded through conduit to protect it from the elements.

Various network connection, power generation, communications permissions, and administration issues delayed DCPH coming back online for 11 years.

In 2019, our field team wired the seismic instruments to the Coast Guard facility, but there were still power and connection problems, so no data was flowing.

With stations spread across the state, and a field season limited by Alaska’s short summers, our field team must prioritize which stations they can visit each year and how much time to spend at each. This often means only a couple of days are allotted to repair individual stations. For complex situations like at DCPH, it may take multiple visits across multiple years to work out all the kinks.

The Earthquake Center field team visited the site next in 2023, forewarned by the Coast Guard that another lightning strike had damaged equipment. Nate Murphy, our field network manager, visited DCPH for the first time that year. “There was damage in the comms line between the vault and the Coast Guard station, damage to the circuit breakers, and the vault equipment was fried.” The team was able to fix some of the burned-out gear, but they didn’t have parts to fix everything. The site was still offline.

The team returned in 2024, upgrading equipment and replacing the broken 375-foot-long communications ethernet cable. They dug a shallow trench to bury the communications and power cables to protect them from weather and bears. Weather delays cut short work at the site, so the field team was unable to replace the surge protector required by the Coast Guard. Still no DCPH connection.

The final push

In 2025, the field team returned to find obvious bear damage. “Both conduits were ripped out by bears—the power cable was somewhat intact, but the communications cable was severed,” reported field intern Devin Zigmont. Field technician Ethan Berkeland and Zigmont spent three days on site.

Berkeland decided it was time to try a fiber-optic communications cable. The ability of fiber-optic cable to carry information is not limited by distance. It also has the bonus of being unable to carry a charge, unlike ethernet cables—which is helpful in this lightning-prone spot. It was no easy fix. It’s a delicate operation to thread the cable through such long conduit. “You can’t tug too hard, so we had to cut junctions in the conduit,” Zigmont said. Berkeland said, “We dug a 6-inch deep trench about 375 feet long to protect the power and new fiber-optic communication cables. With the rocky ground, using a pickaxe and a shovel, it was a monumental effort.” (Figure 5).

A monumental effort indeed! After years of work by many different dedicated Earthquake Center staff members, DCPH has finally rejoined the Earthquake Center network. As we move toward earthquake early warning in Alaska, DCPH will fill a crucial place keeping an eye on earthquakes from the variety of faults in this active region.