Glaciers

Earthquake Center seismic stations record hundreds of small quakes annually in Alaska from a source you may not expect: glaciers. On average we detect between 1,500 and 2,000 glacial quakes (sometimes called ice quakes) per year. They range in magnitude, some comparable to magnitude 3 earthquakes. Over the past decade or so our glacial quake data has grown from a scientific curiosity to a useful tool for tracking certain glaciers.

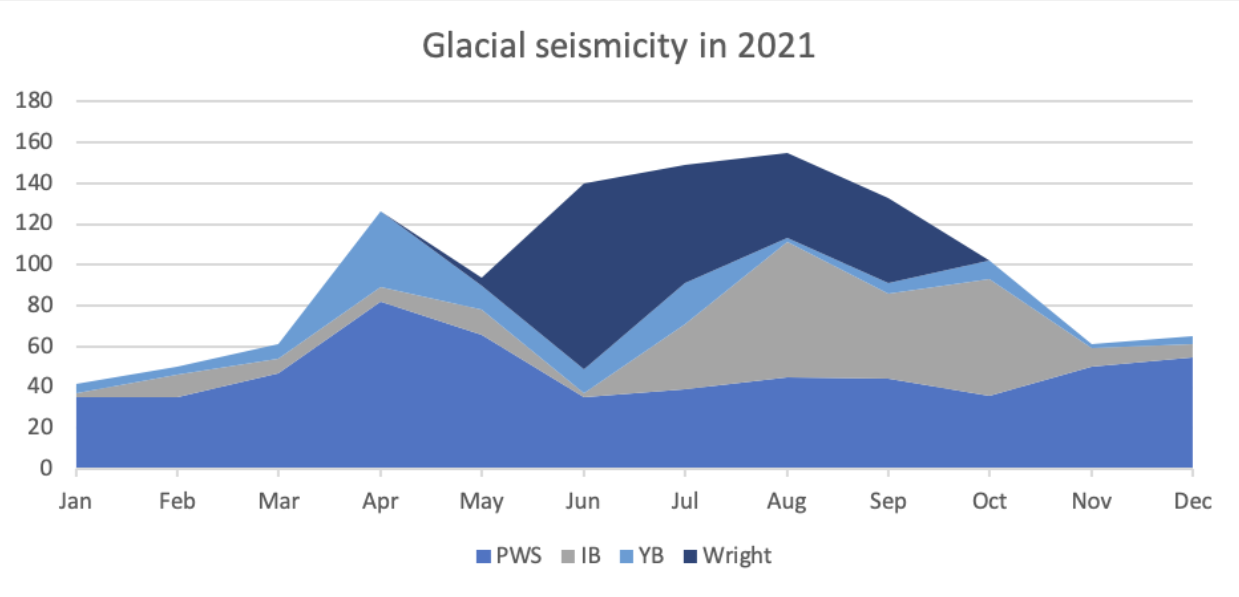

We record the majority of glacial activity in the Prince William Sound region, Icy Bay, and Yakutat Bay. However, in 2020 an unusual cluster of approximately 350 glacial quakes occurred July-September under Wright Glacier about 40 miles northeast of Juneau. A few of these events reached a magnitude between 3.0-3.4 and were felt in Juneau. Periodic seismicity in this area has been observed since the 1970s. While the event rates are highly variable each year—the high seismicity rates observed in 2020 and 2021, for example, have not been observed since 2011-2012—activity usually peaks in summer and early fall. These quakes tend to cluster near the Speel River, where it drains glaciated areas of Mt. Ogden.

Glacial quakes are highly seasonal, generally ramping up in April and falling off sharply in October. Glaciers move more when the weather is warm, as melt water and rain lubricate and float the bed of the glacier. Most glacial quakes we report are caused by large icebergs calving into open water at the terminus, or end, of a glacier, typically where it enters the ocean. Some of these massive splashdowns can be detected a couple hundred miles away. Glaciers also create seismic events (ground shaking) through crevassing, grinding against underlying rock, and toppling pieces off of steep glacier ice falls.

A few of these "noisy" glaciers are located inland where they cannot have a tidewater terminus. Tana, Wright, and Brady are examples. Research has demonstrated that large glacial quakes occur when icebergs fall intact from height into bodies of water. It turns out these noisy inland glaciers all have lakes at their terminuses, allowing them to create calving glacial quakes similar to what we see in the ocean. This is important because it suggests that most glaciers might have the right conditions to create large glacial quakes at some point in their existence. It also explains why we shouldn't immediately write off the occasional glacial quake in the Alaska Range or other land-locked areas.

Seismograms from Mt. Ogden show how glacial quakes have different characteristics than typical tectonic earthquakes. Glacial quakes have emergent (non-impulsive) seismic arrivals, which tell us that the source of these events has more gradual build up, as opposed to the sudden energy release of a tectonic earthquake. The seismogram also displays monochromatic waveforms, which do not have a wide variety of frequencies, indicating the seismic waves are generated with the presence of fluids. Lastly, these signals are lower frequency than typical tectonic earthquakes.

PWS - Prince William Sound; IB - Icy Bay; YB - Yakutat Bay; Wright - Wright Glacier in Southeast Alaska.

Explore More

Muldrow Glacier Surge in 2021

Quakes near Pothole glacier

What is causing seismicity near Mt. Ogden in Southeast Alaska?