Every year, the Alaska Earthquake Center issues new maps and reports that detail the history and hazards of tsunamis in a handful of coastal communities. And every year, Earthquake Center tsunami scientist Elena Troshina travels to those communities to explain the report results. This January took her and a team of tsunami and hazard specialists to Metlakatla, the southeasternmost community in Alaska.

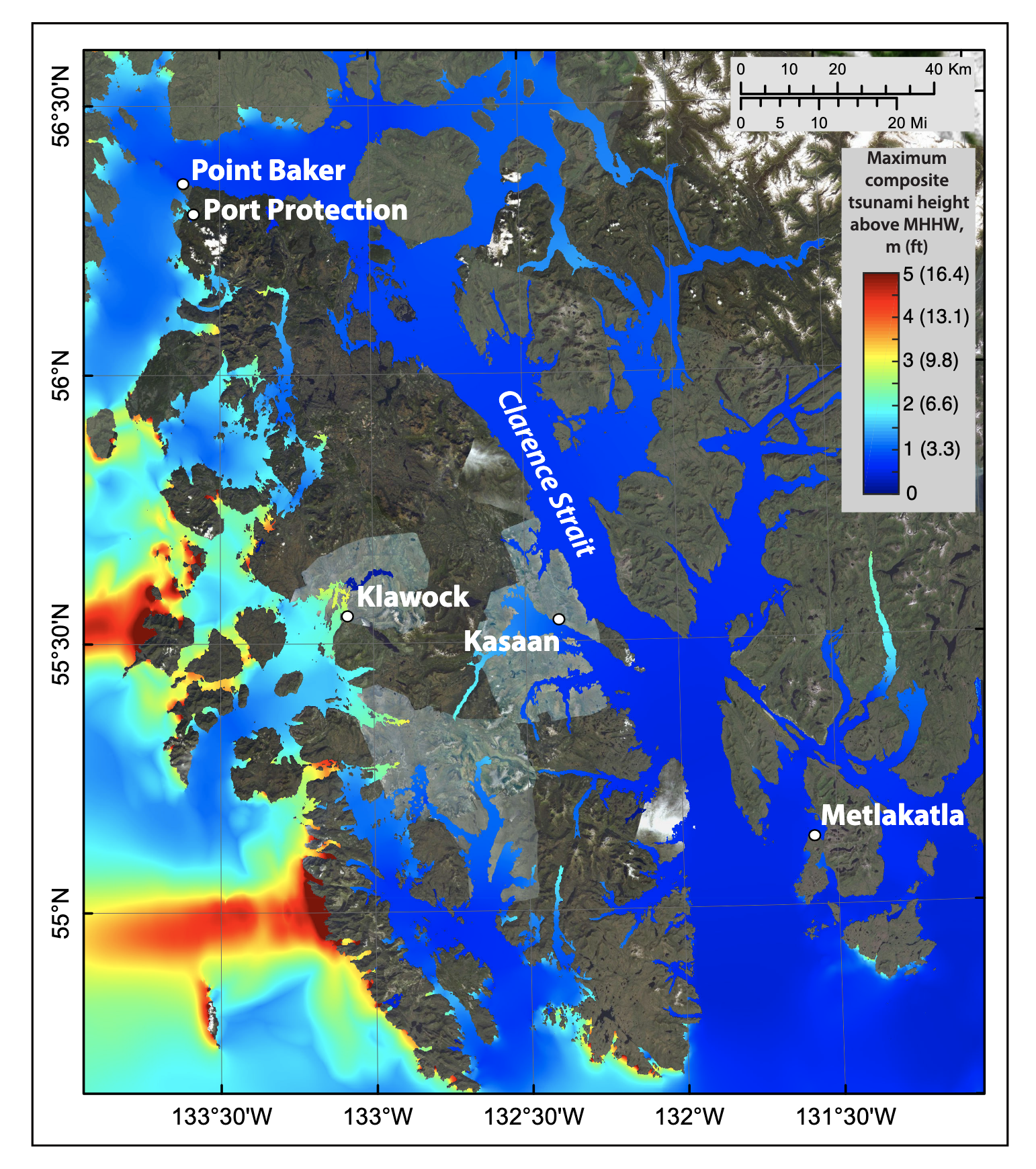

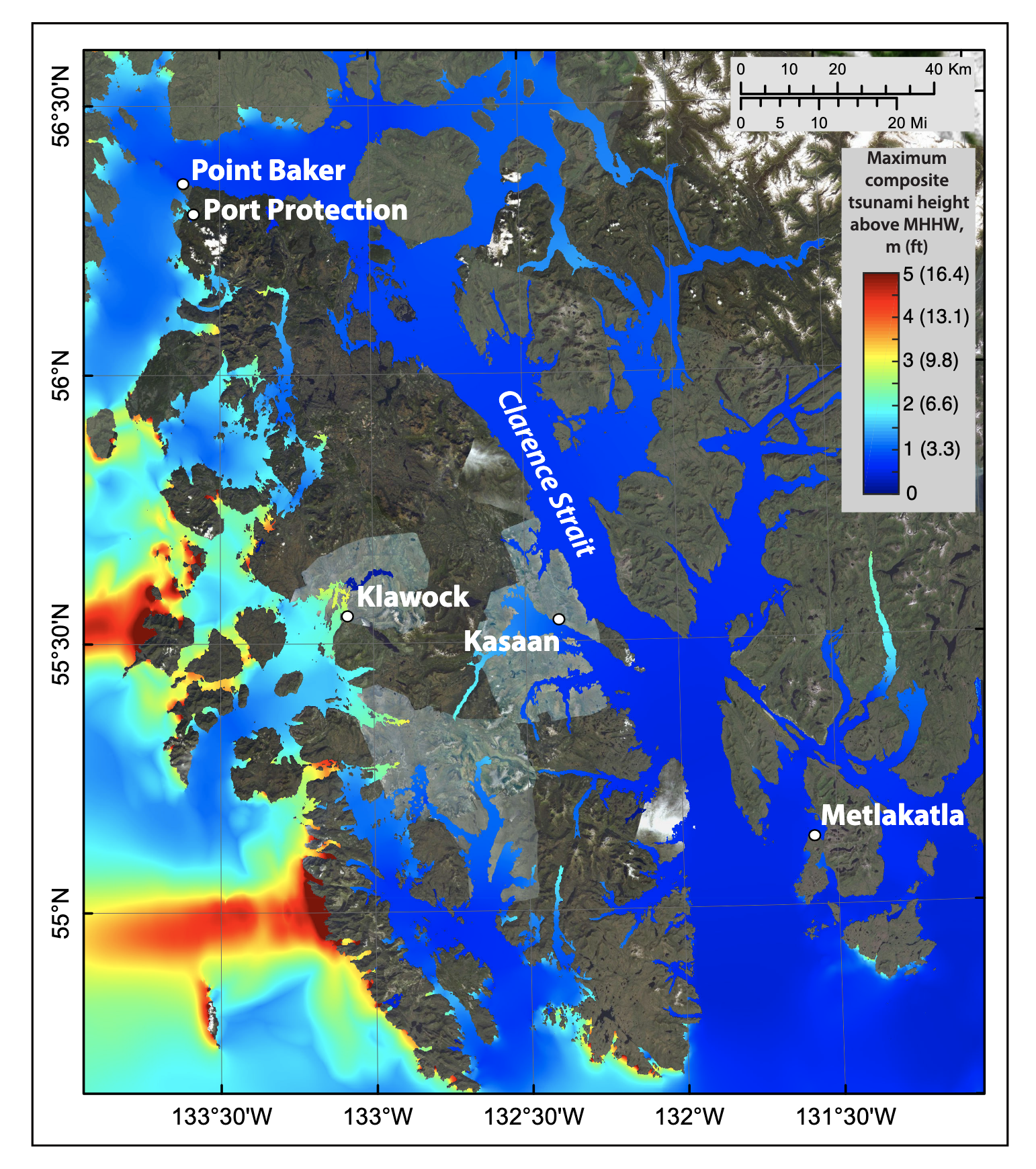

The visit was long overdue, since Metlakatla’s tsunami mapping report was published in 2020, along with those for five other Southeast Alaska communities. “But then Covid happened,” says Troshina. In the past four years, community planners have been busy responding to the information provided by the new tsunami hazard modelling and mapping efforts. “They knew they needed to establish their evacuation zone,” says Troshina. “They have plans to relocate local government offices and their senior center to higher ground.”

Offshore risks are also of heightened concern for this Tsimshian community, as Metlakatla divers are often in the water harvesting sea cucumbers.

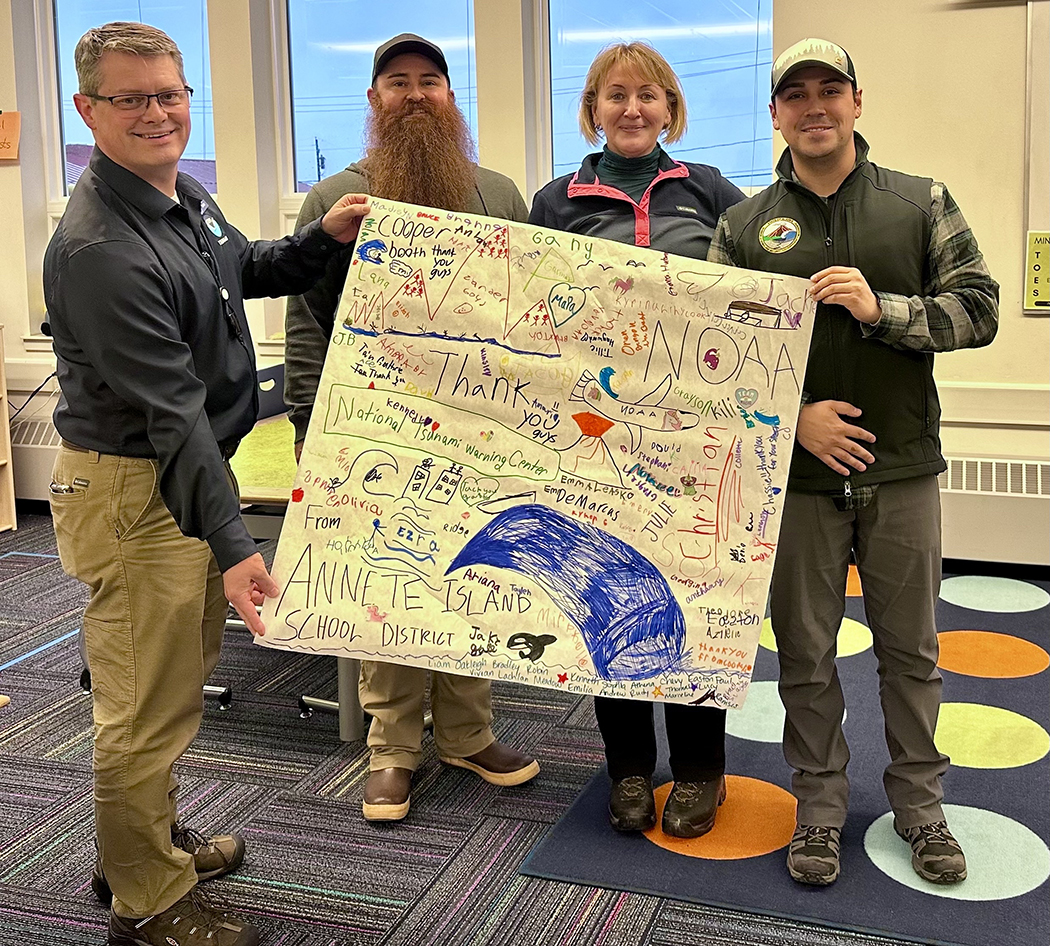

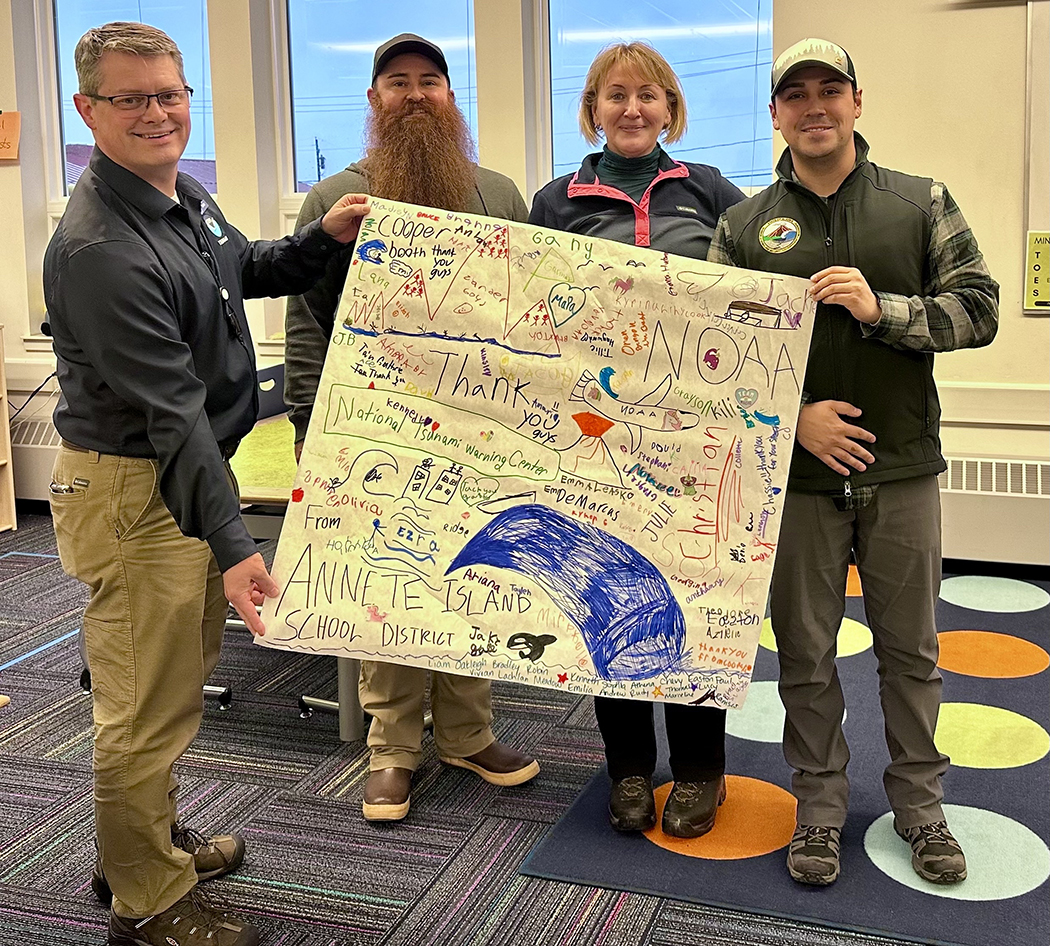

Troshina worked with the community leaders of Alaska’s only Indian Reserve—as well as representatives from the Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys, the National Tsunami Warning Center, Alaska’s Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, and NOAA—to re-plan the meeting. That meant not only lining up personal schedules, but also working around the seasonal commitments, like fishing, of the Metlakatla Indian Community.

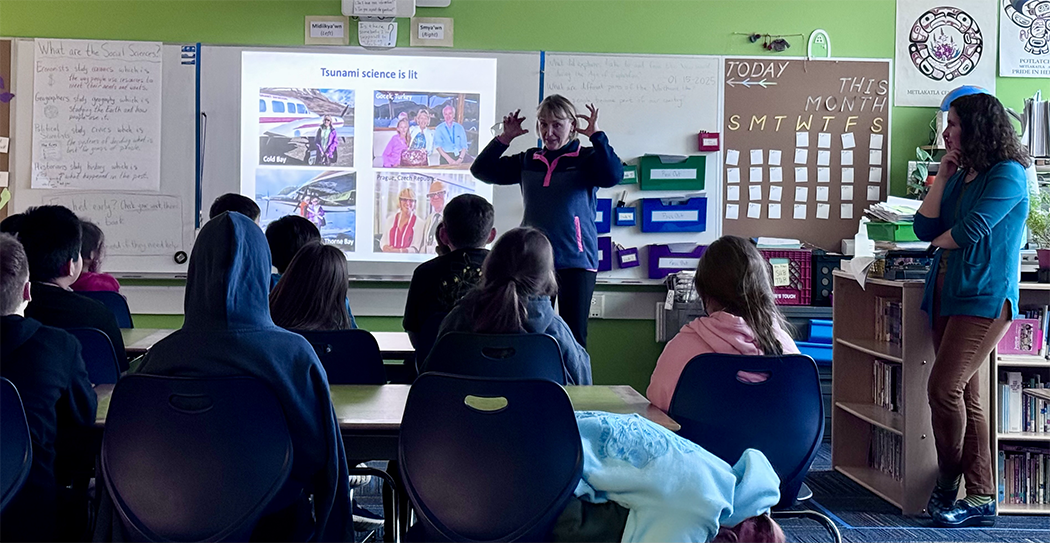

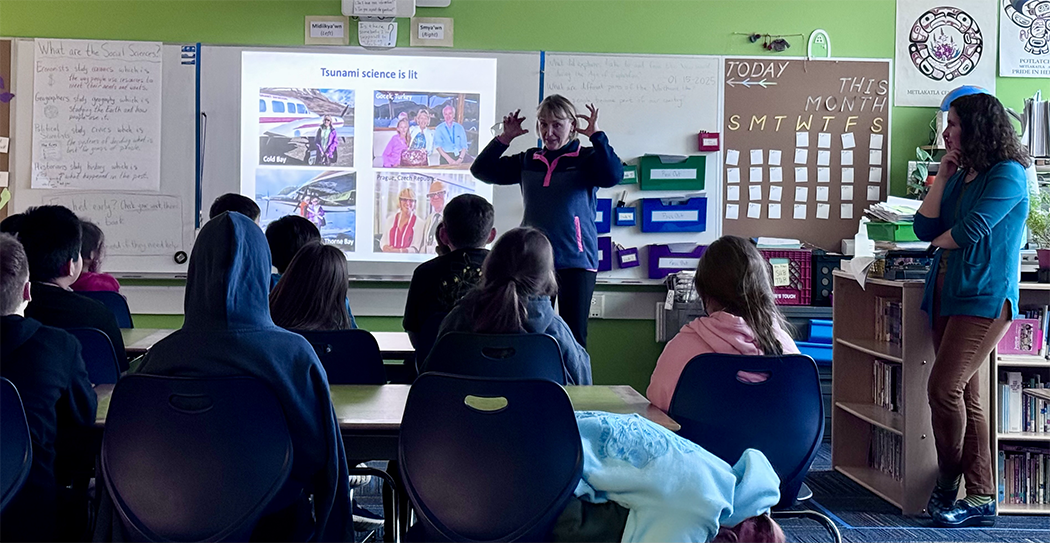

“We explain to emergency officials what the results mean, and try to educate the community about tsunami hazards in the area,” says Troshina. This includes community and school presentations. Troshina was particularly impressed with Metlakatla’s level of hazard awareness and scientific knowledge, from quiet and receptive kindergarteners to organized community planners. “They were well-prepared, knowledgeable and appreciative of the hazard facing their community.”

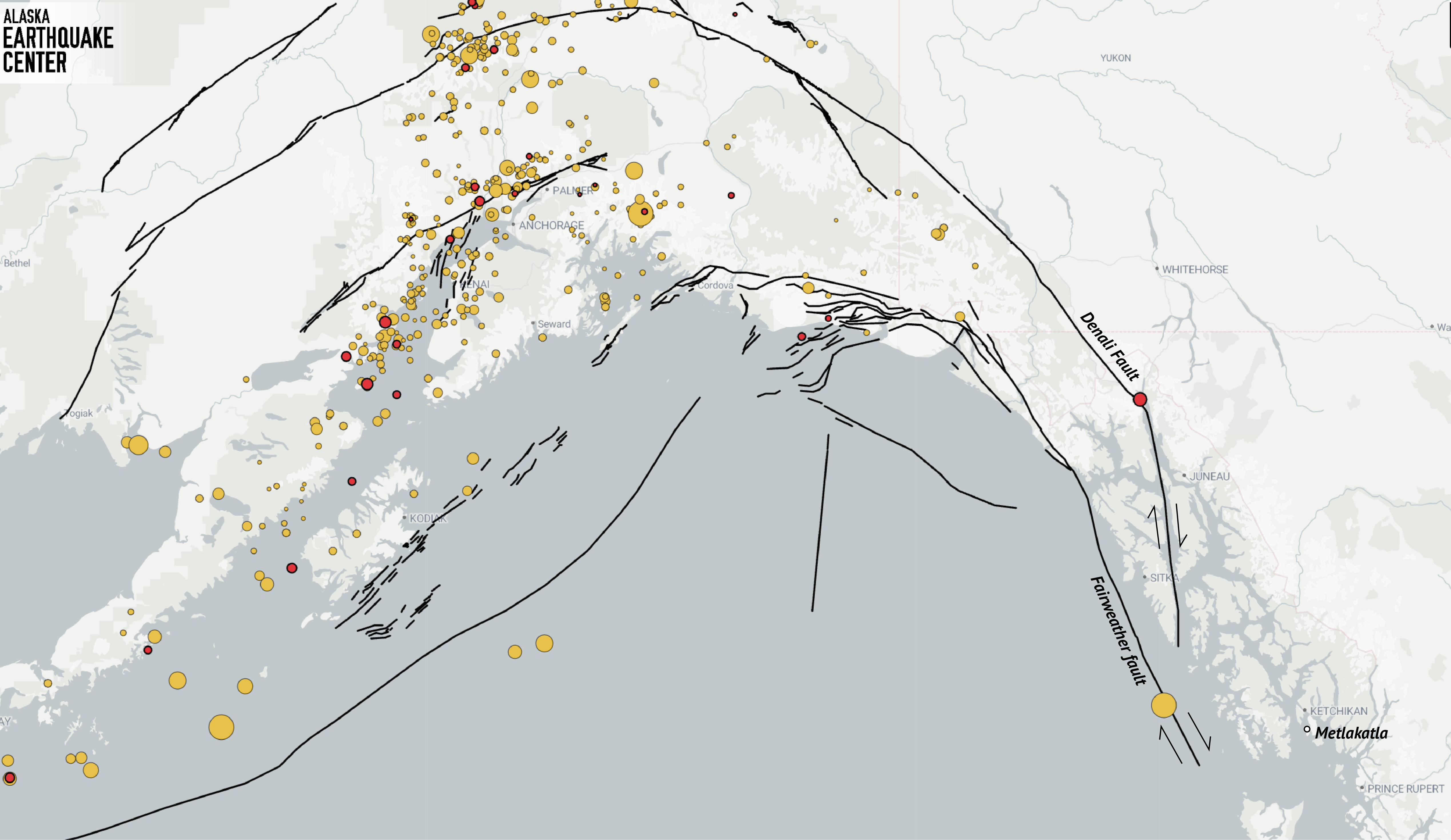

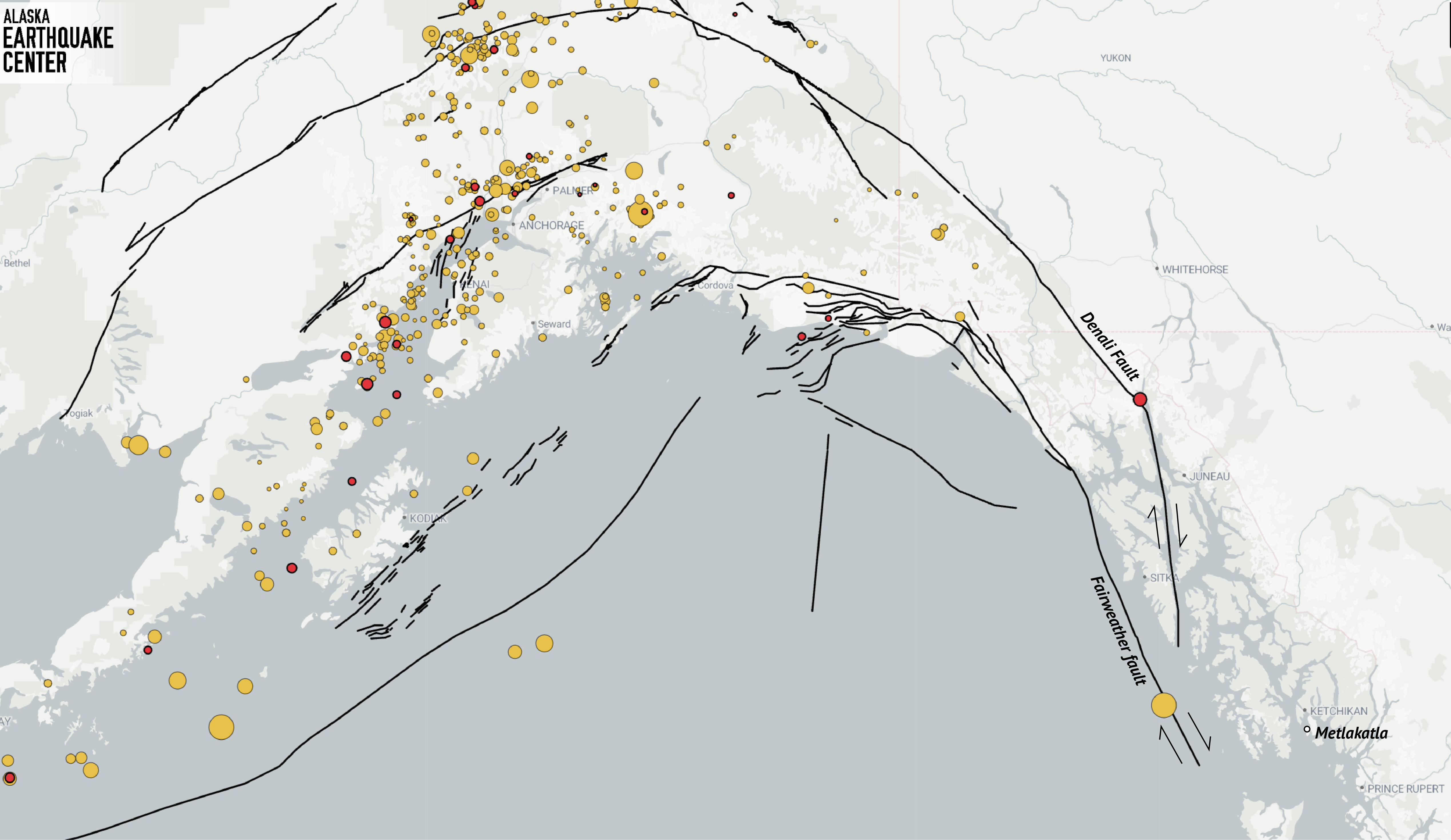

Despite Metlakatla’s proximity to a major active, undersea fault, the village actually has a somewhat lower modeled tsunami hazard. This is mainly because the Queen Charlotte Fault is strike-slip, with lateral motions that don’t typically move the volume of water that a thrust fault would in a similar setting. However, Troshina says that the only hazard the team assessed was from tectonic tsunamis, adding, “this is only based on what we know today. We don’t know what all the earthquake scenarios for this community are.” The modeling is based on current understanding of worst-case scenarios for fault rupture, but excludes tsunamis caused by possible landslides.

Because of this, community planners chose conservative action, placing their evacuation line at the 50-foot elevation, because they understood the limitations and uncertainties of modeling. To determine this line, they worked with a new, interactive, web-based map tool, developed by Alaska Earthquake Center collaborator Dmitry Nicolsky and his undergraduate student Levi Anderson to enable communities to map out their own choices. In the next step, Earthquake Center and UAF staff will work with Metlakatla officials to design and publish a tsunami hazard brochure, including the evacuation line drawn by the community, in order to distribute this important information.

This project is funded by the NOAA’s National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program, in cooperation with Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys and Alaska Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management.